The Thai performing arts stand as a vibrant and enduring expression of the nation’s cultural heritage. With roots reaching back thousands of years, these art forms have evolved alongside Thailand’s history, blending tradition, spirituality, and artistic refinement. From graceful classical dances and energetic folk performances to contemporary reinterpretations, Thai performing arts offer a rich and diverse landscape that reflects the values and creativity of the Thai people. This article will take you through an overview of Thailand’s performing arts heritage.

Photo credit: Department of Cultural Promotion, Thailand

Defining Thai Performing Arts

The Thai term for performing arts is “natasin / natasilp” (นาฏศิลป์), derived from the Sanskrit words nata (dance or performance) and śilpa (art). Thus, it can be translated as “the art of dance and dramatic performance.” However, Thai performing arts encompass far more than just movement. They represent a synthesis of music, narrative, costume, gesture, and ritual. Together, these elements create a deeply expressive art form that reflects Thai aesthetic ideals, spiritual beliefs, and cultural values.

Photo credit: Thaipost

To understand what constitutes “Thai” performing arts, one must also consider the evolving definition of “Thai.” Today, “Thai” refers broadly to the peoples of Thailand, a multiethnic society comprising Central Thai, Northern (Lanna), Northeastern (Isan), Southern Thai, and numerous other ethnic groups, including Mon, Khmer, Malay, Karen, and Lao, among others.

Photo credit: krupanomporn

Therefore, Thai performing arts should be understood not as a monolithic tradition, but as a collection of diverse performance practices rooted in the many cultural communities across Thailand, as well as in Thai diaspora communities abroad. These forms range from elegant royal court dances to vibrant folk performances and contemporary reinterpretations, all contributing to the richness of Thailand’s artistic heritage.

History of Thai Performing Arts

The history of Thai performing arts stretches back thousands of years, deeply intertwined with spirituality, courtly culture, and evolving global influences.

Prehistoric Roots: Rituals and Spirituality

The earliest evidence of performing arts in what is now Thailand dates back to prehistoric times. Cave paintings and bronze drums suggest that early communities incorporated movement, rhythm, and sound into sacred rites. Figures depicted in the crouched “frog posture,” as noted by Thai historian Sujit Wongthes, likely represent dance-like gestures used in animist rituals, including rainmaking and spirit summoning.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Instruments such as the bronze drum (กลองมโหระทึก), often adorned with frog imagery, reflect the symbolic association of frogs with rain and fertility. These early performances were also linked to the ancient belief in khwan (ขวัญ), the vital life-force believed to safeguard health and well-being. Drumming and ritual noise were used to call back lost khwan, making performance an early form of spiritual healing.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Early City-States: Indian Influences

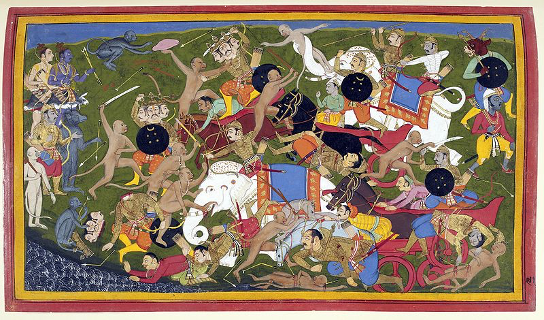

In early kingdoms such as Dvaravati (6th–11th century CE), Srivijaya (7th–13th century CE), and the Khmer Empire (9th–15th century CE), performing arts developed as a part of statecraft and religious life, heavily influenced by Hindu-Buddhist traditions from India. Temple carvings from these periods depict dancers, musicians, and ritual processions, indicating that music and dance played a central role in religious ceremonies, royal rituals, and storytelling, especially through epics like the Ramayana.

Photo credit: Bloggang

Tai-Speaking Kingdoms: Tai Identity and Elements

As Tai-speaking kingdoms such as Sukhothai (13th–15th century CE), Lanna (13th–18th century CE), and Lan Xang (14th–18th century CE) emerged, they incorporated and reinterpreted these earlier cultural influences, blending Mon-Khmer and Indian elements with Tai elements. Performing arts became integral to Buddhist festivals, merit-making rituals, and royal court ceremonies. The use of Tai-Lao languages in songs, chants, and narratives helped forge a unique cultural identity that remains central to Thai performance traditions.

Photo credit: Travel 360

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Ayutthaya: Courtly Splendor

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (1351–1767) marked a golden age of courtly performing arts. Under royal patronage, the arts flourished as both state ritual and political spectacle, showcasing the kingdom’s wealth and refinement. Grand performances were central to royal ceremonies, state diplomacy, and religious festivals. Highly trained artists served in the court, producing sophisticated art forms such as Lakhon (ละคร), or narrative dance-drama, and Khon (โขน), the elaborate masked dance-drama based on the Ramakien, the Thai version of the Hindu epic Ramayana.

Photo credit: iStock

Photo credit: Thaipost

Thonburi and Early Rattanakosin: Restoration and Refinement

After Ayutthaya’s fall, the short-lived Thonburi Kingdom (1767–1782) under King Taksin worked to revive these traditions. In the early Rattanakosin period (1782–1851), during the reigns of Rama I, Rama II, and Rama III, the royal court robustly compiled, revised, and expanded classical scripts, while encouraging new compositions. This era saw the artistic zenith of both Khon and Lakhon, which were refined into the forms most recognizable today, with perfected choreography, costuming, music, and narrative structure.

Photo credit: PR Bangkok

Modern Era: Adaptation, Decline, and Revival

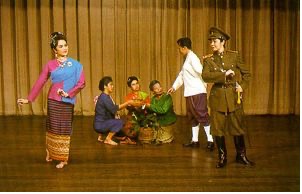

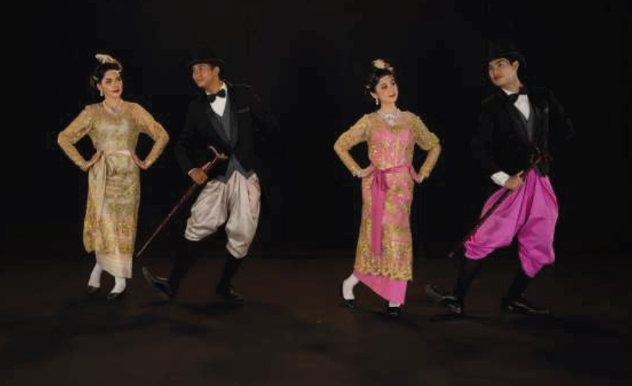

The mid-Rattanakosin period saw growing Western influence, particularly under King Rama IV (1851–1868) and King Rama V (1868–1910). New theatrical forms like Lakhon blended Western operatic structures with Thai traditions, introducing more realistic staging and musical innovations.

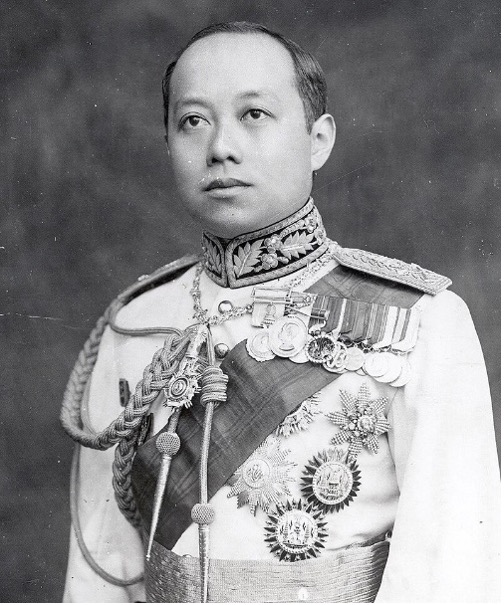

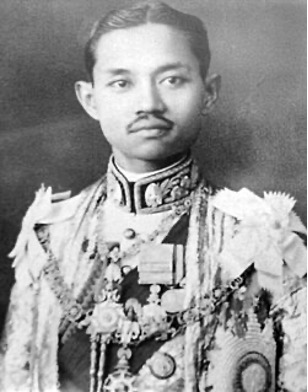

Under King Rama VI (1910–1925), a period often called the golden age of Thai theater, Western, Indian, and traditional influences merged. A passionate playwright, Rama VI composed a large number of plays, introduced spoken dramas such as Lakhon Phud, and translated major Western works into Thai verse. However, during King Rama VII’s reign (1925–1935), political instability and financial difficulties led to a decline in royal patronage, and modern entertainment like cinema began to overshadow traditional performances.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Photo credit: Saranukromthai

In the late 20th century, during King Rama IX’s reign (1946–2016), major revival efforts were launched. The Fine Arts Department and educational institutions conducted formal training programs, while Queen Sirikit’s patronage of Khon elevated it to Thailand’s most prestigious national stage.

Photo credit: Royal Office

Photo credit: Thailand NOW

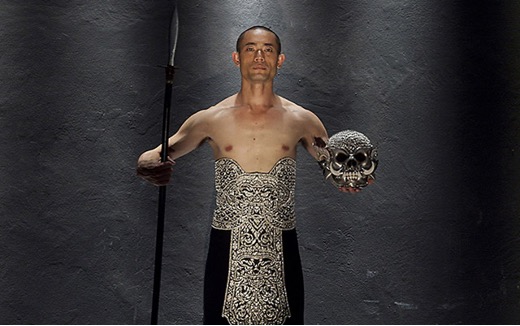

Contemporary artists such as Pichet Klunchun reinterpreted classical traditions for modern audiences, blending centuries-old disciplines with new artistic expression while remaining rooted in Thai identity. In the present day, under King Rama X, who himself has received training in Khon, Thai performing arts continue to thrive through both preservation and creative innovation.

Photo credit: Art Bangkok

Categories of Thai Performing Arts

Classifying Thai performing arts is not a simple task. Across centuries of development, numerous forms of dance, drama, and music have emerged throughout different regions, social classes, and historical periods. Many of these forms overlap, blend, or borrow from one another, making it difficult to fit them neatly into rigid or uniform categories. Nevertheless, one useful way to approach this complexity is to view Thai performing arts through three broad categories: classical, folk, and creative (contemporary) forms.

Photo credit: Office of Art & Culture Chulalongkorn University

1. Classical Performing Arts

Thai classical performing arts refer to performance traditions that have been refined over centuries under royal patronage and courtly institutions. They follow formalized principles of choreography, costume, music, and stagecraft, and are deeply rooted in ancient aesthetics and spiritual symbolism. The main classical forms include:

Ram (รำ): solo or duet dances with standardized graceful movements, often used for practice or ceremonial openings.

Photo credit: Nattasinn

Rabam (ระบำ): group dances, often performed without a narrative plot. They can be further divided into: Rabam Mat-tra-than (ระบำมาตรฐาน), or “Standard Rabam,” with fixed choreography and costume conventions; and Rabam Bet-ta-led (ระบำเบ็ดเตล็ด) “Miscellaneous Rabam,” with diverse and creative variations.

Photo credit: blogspot

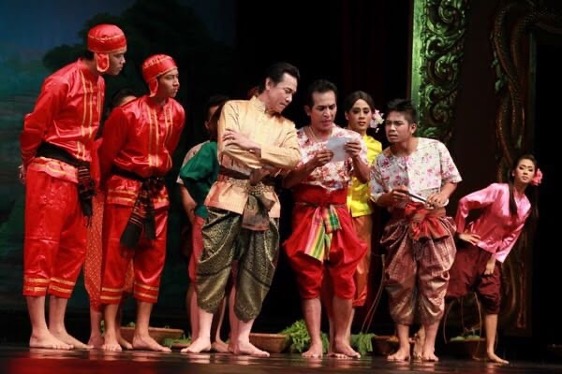

Lakhon(ละคร): narrative dance-dramas that portray stories through dance, song, or speech, divided into: Lakhon Ram (ละครรำ), which focuses on choreography; Lakhon Rong (ละครร้อง), which focuses on singing; and Lakhon Phud (ละครพูด), which focuses on dialogue.

Photo credit: สวท.กาฬสินธุ์ กรมประชาสัมพันธ์

Khon (โขน): the highly elaborate masked dance-drama based on the Ramakien, combining stylized movement, off-stage narration, and elaborate costuming. Khon itself includes several sub-forms including Khon Klang Plaeng (โขนกลางแปลง), or “Outdoor Khon;” Khon Nang Rao (โขนนั่งราว), or “Rail-Seated Khon;” Khon Rong Nai (โขนโรงใน), or “Inner Stage Khon;” Khon Na Jor (โขนหน้าจอ), or “On-Screen Khon;” Khon Chak (โขนฉาก), or “Multi-Scene Khon.”

Photo credit: Bangkok Post

Photo credit: National Geographic Thailand

Photo credit: KONKHON

2. Folk Performing Arts

Folk performing arts reflect the regional diversity of Thailand, shaped by local traditions, languages, occupations, and spiritual beliefs. Unlike the highly codified classical forms, folk performances often emphasize communal participation, oral tradition, and connections to seasonal or spiritual events. Folk dances are typically grouped by regional culture:

Northern Thailand (Lanna): characterized by graceful and slow-paced dances such as Fon Leb (Fingernail Dance), Fon Thian (Candle Dance), and Fon Jerng (Martial Dance).

Photo credit: Facebook

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Northeastern Thailand (Isan): characterized by energetic and rhythmic dances such as Serng Pong Lang (Xylophone Dance), Fon Phu Thai, and Krathop Saak (Pestle Dance).

Photo credit: Isan Club Chula

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Central Thailand: characterized by lively and festive dances reflecting agricultural life, such as Ram Wong (Circle Dance), Ram Thoet Thoeng (Long Drum Dance), and Rabam Chao Na (Farmers’ Dance).

Photo credit: Sunita

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Southern Thailand: characterized by vigorous dances such as Nora (UNESCO-listed), Ronggeng, and Tari Bu-nga (Southern Bouquet Dance), often blending Buddhist, Malay, and Islamic cultural influences.

Photo credit: International Cultural Heritage of Thailand

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

3. Creative (Contemporary) Performing Arts

In recent decades, Thai performing artists have embraced creative performing arts, combining traditional techniques with modern stagecraft, thematic innovation, and cross-cultural inspiration. These works often draw from classical and folk sources but reinterpret them for contemporary audiences, both domestic and international.

Photo credit: Wiphitsilpa

4. Other Performing Arts

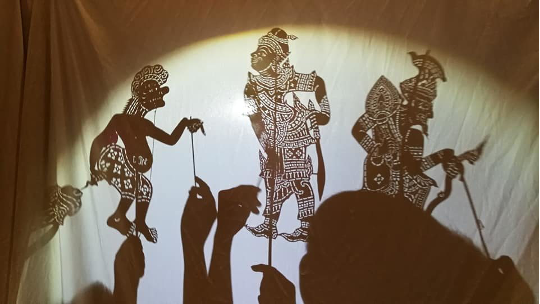

In addition to classical, folk, and creative categories, Thailand is home to many other distinctive performance forms that enrich its cultural landscape. These include, but are not limited to, Likay (ลิเก), a lively folk opera blending singing, dancing, and humor; Nang Yai (หนังใหญ่) and Nang Talung (หนังตะลุง), forms of shadow puppetry featuring intricately carved leather figures; Hun (หุ่น), various traditions of refined puppetry; and various comedic stage performances or Jam Uad (จำอวด) known for their improvisation and satire.

Photo credit: Thaipost

Photo credit: Anurak Magazine

Photo credit: Silpa-Mag

Characteristics of Thai Performing Arts

At the heart of Thai performing arts lies an aesthetic ideal known as on-choi (อ่อนช้อย), which may be translated as elegant, flowing, and refined. This graceful quality runs through every aspect of performance, including:

Choreography: characterized by controlled, symbolic gestures that often unfold at a deliberate pace. Each motion is carefully composed to convey emotion, character, or narrative symbolism.

Photo credit: Sanook

Costumes: elaborate and meticulously crafted, reflecting regional variations, historical periods, and the roles of the performers. Whether it’s the richly adorned Khon masks or the colorful textiles of regional folk dances, costume design plays a vital role in conveying cultural identity and visual splendor.

Photo credit: Canon Snapshot

Music: serves as a live, ever-present partner to the performance, typically provided by traditional Thai ensembles such as the Piphat or Mahori orchestra. The musicians set the rhythm, mood, and emotional tone, working in close synchronization with the dancers.

Photo credit: Thailand Music Project

Photo credit: Thailand Music Project

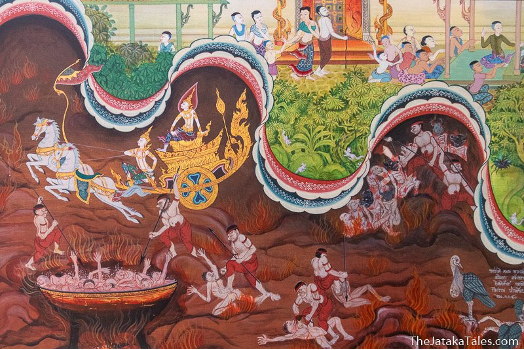

Narratives: in Thai performing arts, these are often drawn from mythological epics, Buddhist Jataka tales, or moral stories, written in beautiful poetic forms. The interplay of verse, movement, and music brings these stories to life, offering both entertainment and moral reflection to audiences.

Photo credit: thejatakatales

Aside from aesthetic ideals, Thai performing arts are also highly spiritual. For many practitioners, performing arts are not merely artistic pursuits, but a deeply embedded way of life that encompasses spiritual devotion, discipline, and cultural responsibility. Artists live by strict codes of behavior, purity, and respect, upholding traditions passed down through generations.

Central to this tradition is the reverence shown toward teachers, or khru (ครู), who are seen as both mentors and spiritual guides. The Wai Khru (พิธีไหว้ครู) ceremony is held regularly, allowing performers to pay homage to their teachers and the sacred lineage of their art. Before major performances, rituals and blessings are often conducted to seek protection and ensure a successful show, reflecting longstanding beliefs in spiritual forces that influence the arts.

Photo credit: The National Theatre

Cultural Values Reflected in Thai Performing Arts

Behind the characteristics, Thai performing arts serve as a living reflection of the values that shape Thai society and cultural identity.

Refinement: The meticulous detail seen in choreography, costume, and music reflects the refined artistic sensibility of the Thai people. Every gesture is carefully composed, every costume intricately crafted, demonstrating not only artistic skill but also a national appreciation for beauty, delicacy, and discipline. This refinement is not merely decorative but expresses the cultural ideal of composure, grace, and dignity.

Photo credit: Kampatour

Harmony:The coordinated interplay between dancers, musicians, and narrators embodies the Thai value of harmony, both within the performance and in society at large. Whether in the synchronized flow of group dances or the balance of rhythm and melody, performances emphasize cooperation, unity, and the smooth blending of elements, mirroring the social ideal of peaceful coexistence and mutual respect.

Photo credit: nitasrattanakosin

Respect:Thai performing arts are deeply rooted in traditions of respect and spiritual devotion. Central to this is the profound reverence for teachers who are seen not only as instructors but as spiritual guides preserving sacred knowledge. Ceremonies such as the Wai Khru (พิธีไหว้ครู) embody this respect, as performers pay homage to their teachers and the lineage of artists who came before them. Beyond the teacher-student relationship, performers also observe rituals and seek blessings before major performances, acknowledging spiritual forces believed to govern success, protection, and artistic purity. This combination of discipline, humility, and spiritual mindfulness underscores the deeper purpose of performance as both an art form and a sacred practice.

Photo credit: Chulalongkorn University

Openness to Outside Influence: While firmly rooted in tradition, Thai performing arts have consistently shown an openness to other cultural influences. Whether seen in the adoption of Hindu epics or Western stagecraft, this ability to absorb and reinterpret external influences has allowed Thai performing arts to continually evolve while preserving their distinct identity.

Conclusion

Thai performing arts are far more than entertainment; they are living reflections of Thailand’s history, values, and spiritual traditions, blending grace, discipline, and creativity across generations. From classical court performances to vibrant folk dances and contemporary interpretations, each form offers a unique glimpse into the Thai way of life. We invite you to explore this rich cultural heritage, to witness its beauty, and to appreciate the generations of artists who continue to preserve and reimagine these timeless traditions.

Photo credit: WordPress

Photo credit: NewsBytes Thai

The Thai performing arts are a profound and living aspect of Thai culture and heritage, reflecting the grace, spirituality, creativity, and enduring values that have shaped the Thai way of life across generations. Join us in exploring more stories of Thailand and the Thai people as we take you on a journey to discover the essence of Thainess.

Sources:

- Wiphitsilpa

- Saithongkham, Chintana, Thai Performing Arts: Ram, Rabam, Khon, Lakhon [นาฏศิลป์ไทย รำ ระบำ โขน ละคร] Bangkok: Bunditpattanasilp Institute, 2019.

- https://www.matichon.co.th/columnists/news_136248

- https://www.thailandfoundation.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Book-WIPITSILPA_lowres.pdf

Author: Tayud Mongkolrat

This article was written with the help of AI.