Thai Lacquerware: From Nature to Fine Art

A Thai lacquerware [cr. Thai PBS]

Lacquering, the art of applying lacquer to the surface of handicrafts and architecture, has long played a significant role in Thai art and craft. This protective and decorative technique has enhanced the appeal of many objects in Thailand, from exquisite Khon masks to magnificent royal barges and gold-gilded pagodas.

Considered a category of Chang Sip Moo (ช่างสิบหมู่) or the 10 Disciplines of Royal Craftsmanship, Thai lacquer is harvested from the gluta usitata tree, also known as the Burmese lacquer tree or Ton Rak in Thai. A glutinous substance, Ton Rak resin makes an excellent coating. Once dry, it is not only shiny, but also resistant to heat and moisture. Thais refer to the art of lacquering as “Ngarn Rak” (งานรัก: literally lacquer works) and to items for which lacquer is predominantly used as “Krueang Rak” (เครื่องรัก: literally lacquerware).

Lacquering: A History

Evidence suggests the art of lacquering originated in China, where some lacquered wooden utensils have been identified as dating back more than three thousand years. It is widely believed that people initially applied lacquer on the surface of many materials as a protective layer. Over time, they developed various techniques that would allow them to use the resin or varnish for artistic purposes.

From China, the art spread to Japan, South Korea, and various Southeast Asian nations including Thailand. A variety of techniques have been used in the creation of lacquerware in Thailand since the era of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1350–1767). The Testimony of Khun Luang Wat Pradu Songtham, which was written between 1732 and 1758, describes many interesting utensils used in Ayutthaya: footed octagonal containers with mother-of-pearl inlay, footed trays featuring lacquer paintings, and gold-gilded Buddha statues, among many others, would only come into service after being lacquered.

The art of lacquering continued over the centuries into the Rattanakosin Era (1782 – present). Lacquering techniques can be seen today in much of Thailand’s splendid architecture and have contributed to the creation of glittering gable apices, superb columns and pillars, and magnificent murals. They also add to the majesty of the Royal Barges, which have been used in grand, state processions since ancient times. The most famous of these is the Suphannahong Royal Barge, the personal barge of the King of Thailand, whose bow resembling a mythical swan is adorned with gold lacquer and glass jewels.

Thai Lacquer Art

In Thailand, lacquerware comes in various forms, and some of the works reflect the very finest of arts and craftsmanship. Five main techniques are used in Thai Lacquer Art, namely, Long Rak Pid Thong (ลงรักปิดทอง), Pradab Krachok (ประดับกระจก), Pradab Muk (ประดับมุก), Lai Kammalo (ลายกำมะลอ), and Khrueang Khoen (เครื่องเขิน).

The first, Long Rak Pid Thong, blends Ton Rak lacquer with gold leaves for gilding the surfaces of furniture, utensils, and religious artifacts. The process of lacquer art starts with the selection of the proper surface materials. Wood, cement, and metal surfaces, for example, can be covered with gold leaves and lacquered. After a material is chosen, its surface must be cleaned thoroughly. Artists and artisans must make sure there is no salinity in the lacquer before applying it. The traditional craft requires that the first layer dry completely before a second coat is applied. This step must be repeated until the surface is smooth. The surface is then covered with a coat of filtered and sun-dried raw resin from Ton Rak. This step is vital in ensuring that the gold leaves will not sink into the surface and lose their glamorous shine. Skills are important here because if the filtered and sundried raw resin is too dry, it will not be possible to place the gold leaves evenly.

A delicate process that makes the exquisite Thai craft possible [cr. Baan Lae Suan]

Gold leaves used for such art works must be pure gold. The rims of gold leaves should overlap by about two millimeters. The placing of the gold leaf is usually done with the lightest touch of the fingers. Where this technique is used on carved sculptures or metal surfaces with elaborate patterns, artisans might also need a brush–big or small–to delicately place the gold leaves along the engraved lines.

Ton Rak varnishing can also be divided into categories based on the area to be covered. These can vary from the entire surface or its smooth parts to patterns on the item’s red background, patterns or gaps on the surface and the background of mosaic decorations.

The second is Pradab Krachok where lacquer is applied alongside mosaic decorations for traditional utensils, architectural details, and Khon apparel. Traditional Thai craftsmanship demands that artisans first coat the surface of the chosen materials with Ton Rak lacquer prior to placing the small glass pieces. When the foundation becomes sufficiently damp, a special mixture of boiled resin and powder obtained from a burnt coconut shell, bricks, dried banana leaf or Rak Samuk is applied. The glass pieces may then be placed. During this process, parts of the mixture will seep between the pieces and form a seal, thus preventing any ingress of water.

Pradap Krachok details on an ogre figure from Wat Phra Kaew [cr. wazzadu.com]

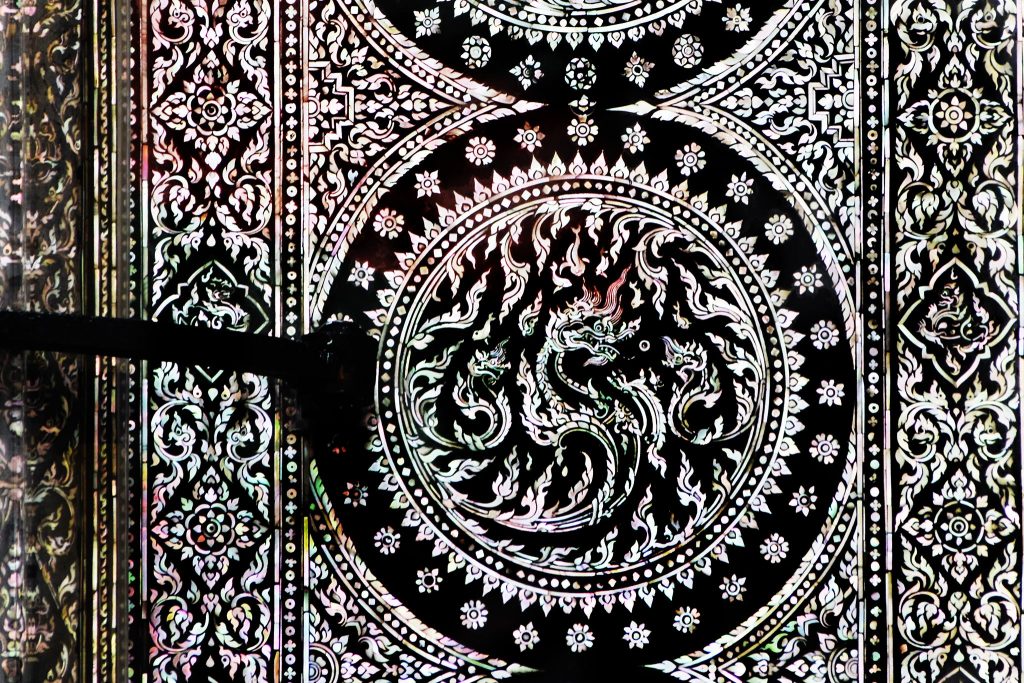

The third, Pradab Muk, involves applying resin of the Ton Rak tree to prime the wood or rattan prior to creating the patterns for mother-of-pearl inlay, an exceptional craft that gets its beauty from the iridescent layer of mussel shells. Mother-of-pearl inlay appears on the gates of Bangkok’s Temple of the Emerald Buddha, which was built in the reign of King Rama I (1782 – 1809), as well as on the gates of Phra Si Rattana Mahathat Temple in Phitsanulok, which was constructed in the Ayutthaya Period.

Pradab Muk details a door panel [cr. FB: Art work of Siam]

Fourth, lacquer painting – also known as Lai Kammalor in Thai – refers to paintings that are created by using a mixture of powdered color and Ton Rak varnish or its filtered, sun-dried raw version. A black resin board is first prepared to serve as the background before the mixture is applied for the painting. Lacquer paintings usually have a gold rim made either with gold leaves or gold powder. In Thailand, lacquer paintings adorn doors, windows, cabinets, and partitions. Sometimes, Lai Kammalor appears on gold-gilded surfaces.

History shows lacquer painting disappeared from Thailand following the fall of Ayutthaya in 1776. King Rama III (1788-1851), however, successfully pushed for its revival, but after his death, the technique began to disappear.

A scripture cabinet with Lai Kammalor decorations [cr. FB: Rhimkobfabooks]

The fifth and final technique, Khrueang Khoen, refers to making wooden/rattan items with Ton Rak resin latex surface that is decorated with motifs created through scratching technique or the application of vermillion or gold leaves. The craft originated from the Tai Khün people, who migrated into Northern Thailand from Kengtung in Shan state, Myanmar. Just like other lacquering techniques, it demonstrates the true spirit of Thai craftsmanship – the respect for natural materials and a keen eye on detailed finesse.

Khrueang Khoen with lacquer and vermilion surface [cr. Channel 7]

Worthy Heritage

An elaborate process, remarkable craftmanship and considerable time are required to create each piece of lacquerware. Thailand, however, has held fast to this traditional art, not only conserving it but also promoting it among new-generation artisans. The various Thai lacquering techniques have continued to produce artistic creations and ensure the heritage from bygone eras is well preserved. Lacquerware creations dating back over the centuries as well as their more modern counterparts are beautiful and truly a sight to behold.

******************************

Reference

Lerdkachatarn, Parisut. Krueng Lacquer Jark Thammachart Su Ngarn Praneed Silpa [Lacquerware: From nature to fine art]. Watthanatham Journal: Department of Cultural Promotion, vol. 52, no. 4, October-December 2013, p. 24-33. Available at Link