Thawan Duchanee: Thailand’s Emperor of the Canvas

A life of a legend with long-lasting legacies.

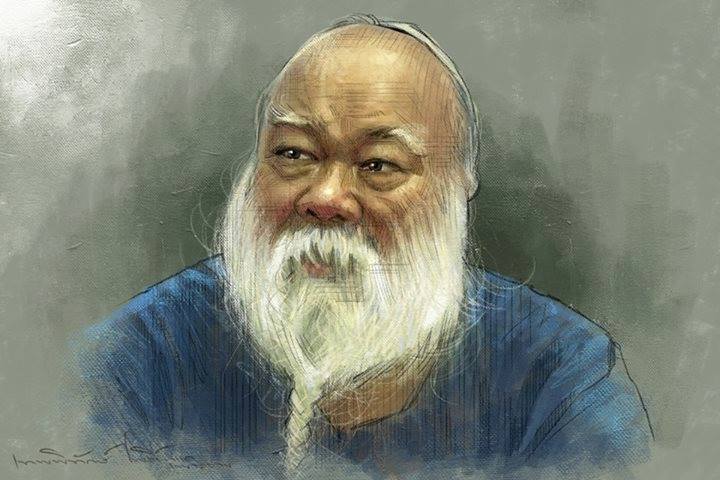

A portrait of Thawan Duchanee [photo: Thawan Duchanee’s Facebook page]

Born in Chiang Rai, Thailand’s northernmost province, in 1939, Thawan Duchanee (ถวัลย์ ดัชนี) was a contemporary artist of international repute. Aside from raising him to the world stage, his works also shook up the Thai art circle thanks to his very different interpretation of Buddhism and daring approach to art.

Thawan’s art journey started while he was still a child. At primary school, Thawan stunned his teachers with his ability to draw almost every character in the Ramayana, the famous epic of ancient India with tens of main characters, each with different extraordinary details.

His obvious talent won him a scholarship to study at Poh Chang Academy of Arts in Bangkok after finishing junior high school in Chiang Rai. “I was the first full-board student at the academy,” Thawan jokingly recalled.

“I was so proud to be a student at Poh Chang Academy of Arts because of my talent. I was very young, not yet 14, when I started at the academy. I was a proud scholarship student. Other friends who came to Bangkok with me went to the royal cadet school and other technical colleges. Those schools have their own dorms. Not my academy. How could I know that my college had no dorm?” he said.

Fearing that his father would be worried if he knew Thawan had no place to stay, Thawan kept quiet about this and decided simply to stay in the college building. He then automatically became the first “full-board student”.

His talent soon became obvious to everyone at the college and his drawing of the Marble Temple (Wat Benchamabophit) in Bangkok was selected for and displayed at the Tokyo National Museum in Japan as well as at the National Contemporary Art Exhibition in Bangkok.

Entering the World of Art

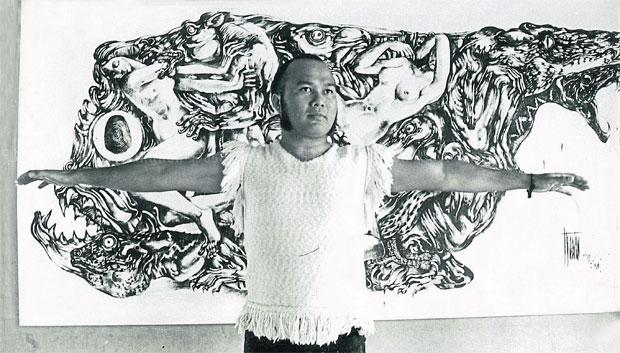

Young Thawan Duchanee [Photo: Bangkok Post]

After graduating from Poh Chang Academy of Arts, Thawan went to the Faculty of Painting, Sculpture and Graphic Arts of Silpakorn University, Thailand’s renowned art university.

“I worked very hard during the first six months because I knew my basics of art were not good enough. My knowledge was limited. Without a true understanding of art, hard work couldn’t help. I failed in many subjects because of repeated mistakes,” he recalled.

At the university, he had a chance to study with the father of Thai modern art, Ajarn Silpa Bhirasri or Corrado Feroci (1892-1962), an Italian artist and a professor who co-founded the university and whose words changed Thawan’s life forever.

“Mr. Mountain Man, you are a hard-working stupid man,” said Ajarn Silpa. “The harder you work, the more you fail. Think before you do things. Don’t work too hard but not be smart.”

Thawan stopped churning out work and started to think more. A year later, he came top of his drawing class. Yet even with his improved works and skills Thawan failed again as his work was not selected for the National Art Exhibition. The reason Ajarn Silpa gave him was simple: “Your work is academically correct but has no life. Your fish cannot swim and have no fishy smell. Your horse is dead, standing dead, no sound, cannot run. Your temple looks like a theatre background. Your sky has no air, cannot breathe. Your painting is not mystic. You don’t understand art, Mr. Mountain Man.”

These harsh comments sparked an understanding, and a new Thawan was born. He took a new approach to art. Over the next few years, his skills improved. Sadly, Ajarn Silpa was not around to see his student flourish: he passed away when Thawan was in his final year and had just received a scholarship from the Netherlands Government to do his Master’s Degree and PhD at Rijks Akademie Van Beelden de Kunsten Amsterdam Nederland.

Life as a Painter

His years in the Netherlands changed his perception and understanding of art.

“Art is like a diamond with hundreds of facets. I knew only one facet. Again, one facet of a diamond can be compared to all the leaves in the forest. I only know one handful of leaves very well, and they are enough to take me to my destination. That’s enough. I know only one facet of the diamond but know it well enough to achieve my goal,” he once said.

It was enough, too: mostly staying home and focusing completely on painting, Thawan did live a happy life.

But while his paintings were appreciated and lauded by many, others did not like his different interpretation of art. Once, his paintings were destroyed while on display at an art exhibition because “he was a mad artist and insulted Buddhism.”

Thawan responded firmly, saying: “I was very clear about my stance. When I returned to Thailand, I told everyone that I felt Buddhist art in Thailand was shallow. Anyone can draw a temple or Buddha images. But for me, I would present only two things about Buddhism – the worldly life and dharma. The worldly and dharma worlds are different but they exist together in the same paintings.”

Nonetheless, Thawan stopped participating in art exhibitions in Thailand for years. “As no one answers my calls, I’d better travel alone.”

Immortal Works

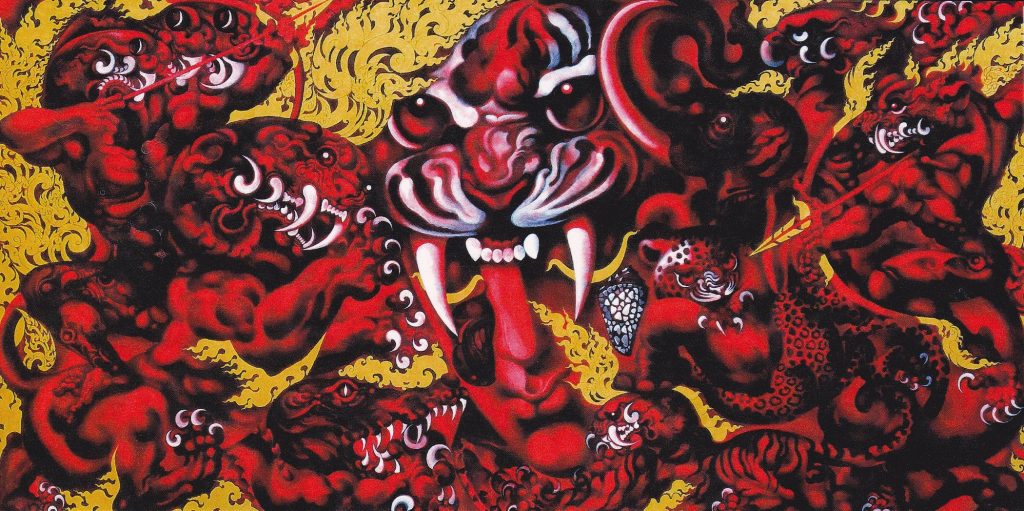

Thawan’s globally acclaimed “Battle of Mara” (2010) [Photo: Thawan-Duchanee.com]

Throughout his journey as a painter, Thawan interpreted and presented his view of Buddhism through contemporary art. By combining Buddhism with eastern and western philosophy, his works developed unique characteristics that appealed to international art advocates. Many of his works are permanently on display in contemporary art museums in Asia, Europe, and the United States.

One of his proudest projects was when he was invited to work in Crottorf Castle, a private museum full of valuable art pieces owned by the Hatzfeldt family in Germany, in 1977 and again in 1985-1986. Count Hermann Hatzfeldt came to Thailand several times on business trips and met Thawan. He was impressed by Thawan’s works and invited him to paint the walls of the castle as part of the family’s collection. Thawan spent 11 months turning the walls of the room at the top of the castle tower into an extraordinary art piece.

A Legacy That Lives On

In addition to creating immortal paintings, Thawan continuously supported art and student development. He set up the Thawan Duchanee Foundation and granted scholarships to talented but poor students that allowed them to attend his old schools, college, and university.

The Black House Museum in Chiang Rai [Photo: Chiang Mai News]

He also built “Baan Dam” (บ้านดำ), the Black House, in his home province’s Nang Lae District. This architectural masterpiece became his home for the rest of his life and was where he created many fantastic art pieces until his death in 2014. Today, it is a famous local art museum where people from all over the world come to appreciate unique art pieces, learn about, and get inspiration from what he left behind.

With art, his life and breath, Thawan continued to paint even when he fell ill. He worked throughout his stay in hospital and his last creation was a painting of a horse.

While the artworks he left behind are valuable and appreciated by art lovers and the general public, Thawan always wanted to retain a low profile, writing in his diary:

“My life is like a rock. When it was first thrown into a pond, it created a ripple effect. The rock then gradually fell to the bottom of the pond, waiting to be covered with lichen and algae. It would soon be lost. No more people think about and talk about it. Let it all end there.”

******************************

Reference

Klomkliang, Pakorn. Thawan Duchanee Jakarapat Bon Puen Pha Bai [Thawan Duchanee: The emperor of canvas]. Watthanatham Journal: Department of Cultural Promotion, vol. 55, no. 4, October-December 2016, p.80-85. Available at http://magazine.culture.go.th/2016/4/mobile/index.html#p=ปกหน้า.