Asalha Puja Day, an esteemed Buddhist festival, takes place on the full moon day of the eighth lunar month, typically falling in June or July. It serves as a commemoration of the Buddha’s First Sermon, also known as Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which he delivered to his five former spiritual companions at the Deer Park (Isipatana) in India back in 600 BCE. This sacred day was officially designated as Dhamma Day in Thailand in 1958 and has since been annually celebrated alongside other important observances such as Vesak Puja Day, Buddha Day, and Magha Puja, Sangha Day.

A large number of Buddhist devotees gathered to celebrate Asalha Puja by participating in the ritual of circumambulating the ordination hall (or Ubosot, a traditional Thai chapel) housing a revered Buddha statue, on Asalha Puja Day at Mable Temple in Bangkok. The purpose was to honor the virtues of the Triple Gem. Engaging in this ritual, they carried joss sticks and flowers as offerings, grasping them as they proceeded to walk three rounds. Throughout the procession, it was essential to cultivate a tranquil mind and recite verses, ensuring remembrance of the Buddha’s virtues, the teachings of the Dhamma, and the noble qualities of the Sangha, until the completion of the three rounds.

This article contains

– The religious beliefs prevalent in India during the time of the Buddha’s birth.

– A summary of the Buddha’s life leading up to his First Sermon.

– The significance of the Buddha’s First Sermon as the direct path to spiritual liberation.

– The transformation of the First Sermon into the celebrated Asalha Puja, now also known

as Dhamma Day.

– How the Buddha taught 84,000 textual units!

– The Buddha’s Messengers of Truth and Compassion.

– A Take-home message.

– References

In honor of this year’s Asalha Puja celebration on July 2nd, 2023, I would like to delve into the historical background of the Buddha’s First Sermon (as for last year’s I wrote this article Asalha Puja Day: Dhamma Day). By exploring this foundation, readers can gain a deeper understanding of the sermon itself and learn from the Buddha’s remarkable ability to effectively convey his teachings. The Buddha skillfully directed his words towards the desired goal, outlined the path leading to it, and successfully implemented this approach. As a result, his five listeners comprehended his new philosophy with clarity. This serves as a valuable lesson for us all, illustrating the importance of establishing clear objectives, identifying the means to achieve them, and executing our chosen methods with diligence and unity.

The religious beliefs prevalent in India during the time of the Buddha’s birth

Between 800-500 BCE in India, when the Buddha came into existence in 563 BCE[1], a diverse range of religious beliefs flourished. One prominent religious tradition was Brahmanism, which emphasized the significance of ritualistic sacrifices and fulfilling religious duties as a means to attain spiritual growth and ultimate liberation, known as moksha. The principles of karma (the law of cause and effect) และ reincarnation formed integral components of Brahmanical beliefs during this era.

Within Brahmanism, the Upanishads emerged later, introducing new philosophical concepts that challenged traditional rituals and stressed the pursuit of knowledge and self-realization. They introduced the notion of atman, the eternal and unchanging self, as well as Brahman the Creator, representing the ultimate reality.

The Upanishadic philosophy viewed life as a transient and ever-changing experience filled with various joys and sorrows. It recognized the cycle of life, death, reincarnation, and subsequent death again (สังสารวัฏ). However, the Upanishads also conveyed that the ultimate aim of human existence is to attain liberation from the cycle of samsara, referred to as moksha. This state is described as supreme bliss, peace, and unity with the creating Brahman.

Various spiritual paths were proposed to achieve union with the Creator (or attain Moksha): (1) the path of selfless action and performing one’s duties without attachment to the outcomes; (2) the path of devotion and love towards a personal deity or the divine; (3) the path of knowledge and wisdom; (4) the path of meditation and contemplation; and (5) the path of self-mortification. The last two of them the Buddha mentioned in his First Sermon.

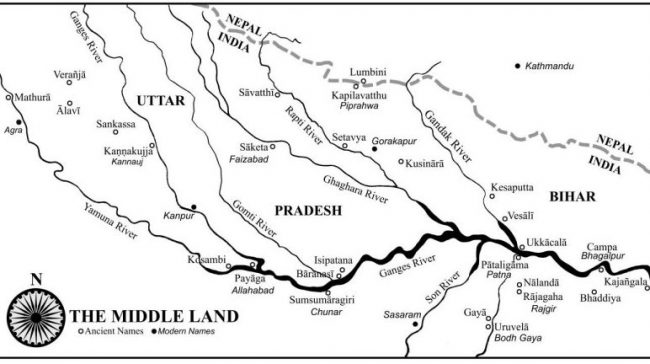

Amidst such religious beliefs, Prince Siddhattha Gotama, also known as Siddhartha Gautama, the future Buddha, was born in 563 BCE into a royal family in the Shakya republic. The capital of this republic was Kapilavatthu or Kapilavastu (modern-day Taulihawa or Tilaurakot in Nepal), located on the border of India. He grew up in a palace surrounded by opulence, experiencing a life of luxury and privilege.

A summary of the Buddha’s life leading up to his First Sermon

Prince Siddhattha possessed a profound interest in spiritual matters. He had acquired extensive knowledge of Brahmanic and Upanishadic scriptures, including the Vedas, Upanishads, and various other sacred texts. Additionally, he demonstrated remarkable aptitude in meditation (samadhi). At the age of 29, he made the decision to leave his palace behind and embark on a journey in search of union with the Creator (or the Path to the Upanishadic Nirvana). It is possible that he explored multiple paths believed to lead to such union or the attainment of Moksha mentioned earlier. These paths encompassed selfless action, meditation and contemplation, and even self-mortification.

On Vishakha Full Moon Day (usually in April-May), he practiced intensive meditation at Uruvela town (modern-day Bodh Gaya), and attained Enlightenment at the age of 35. He became “The Buddha”, “The Enlightened One” or “The Awakened One”. As a result of his Enlightenment, the Buddha proclaimed:

“Rebirth is ended; fulfilled is the holy life; done what was to be done; there will be no more of this state again.”[2]

“Through many lives I sought the one who created the cycles of life and death (samsara) but did not find “him” (craving[3], or Tanha in Pali, is personified as “him” here);. The awareness of suffering overwhelmed me. Now I have seen the one who built this samsara and having seen him, I can ensure the samsara is forever destroyed. All desire has been distinguished, and Nibbana or Nirvana has been attained.”[4]

Following his enlightenment, the Buddha gained a clear understanding that meditation and concentration are effective means to achieve enlightenment. In contrast, he recognized that self-mortification was not a viable path, as he emphasized its futility in his First Sermon.

Moreover, soon after attaining enlightenment, the Buddha contemplated the profundity of the Dhamma (or truth, or succa in Pali) he had realized. He acknowledged that its nature surpassed ordinary logic and comprehension, transcending the understanding achievable by most individuals. However, he believed that there were indeed some highly knowledgeable individuals who could grasp it to some degree. Motivated by this realization, he made the decision to impart his teachings, the Dhamma[5], to others.

To commence his teaching journey, the Buddha chose to share the Dhamma with the five ascetics (known as the Pancavaggiya monks) first. These individuals were not only his trusted spiritual companions but also had been striving for many years to liberate themselves from the cycle of samsara.

At that time, the five ascetics resided in the Deer Park located in Isipatana (modern-day Sarnath), near Varanasi. The Buddha embarked on a journey from Bodh Gaya to the Deer Park (Isipatana), covering a distance of approximately 250 kilometers. It took him a span of two months to reach his destination.

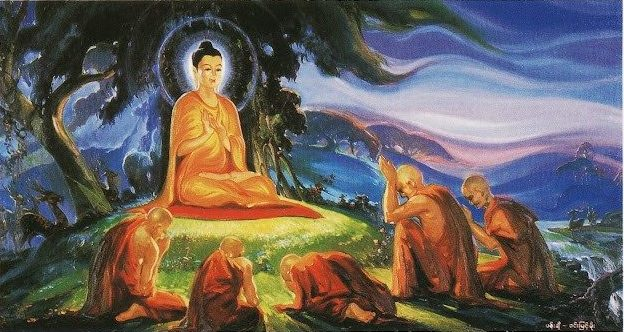

During the auspicious full moon night of Asalha month, at the Deer Park, the Buddha engaged in a collective conversation with his former spiritual companions. In this dialogue, he disclosed that he had achieved Enlightenment, implying that he had discovered the Truth or the Path to Moksha that he had sought, thus liberating himself from the cycle of samsara and attaining liberation form suffering.

Confident in his attainment, the Buddha proclaimed that he had personally reached the destination of Nibbana or Vimutti[6]. He possessed intimate knowledge of the Way leading to this destination and was well-versed in traversing that path. He generously offered to share his profound insights with his companions, assuring them that they too had the potential to attain enlightenment.

Upon their agreement to listen, the Buddha commenced his teachings by delivering the First Sermon. In this pivotal discourse, he elucidated the nature of suffering, its origins, and unveiled the path that leads to liberation from suffering, also known as attaining supreme spiritual happiness.

The significance of the Buddha’s First Sermon as the direct path to spiritual liberation

The Buddha’s First Sermon, known as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta or “The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of Dharma” is significant because it marks the beginning of the Buddha’s teaching career and encapsulates the essence of his teachings.

In this crucial discourse, the Buddha begins by rejecting the belief that indulging in sensory pleasures[7] (which he himself enjoyed as a prince) or engaging in extreme self-mortification (which he underwent after becoming an ascetic) can lead to freedom from Samsara or the attainment of moksha. He shares his personal experience with these two extremes. The Buddha explains that he recognized the errors of both approaches and instead embraced the “Middle Way,” known as majjhimapatipada. He discovered this Middle Path himself and highlights its numerous benefits, such as spiritual insight and intellectual wisdom that enable individuals to perceive things as they truly are. By gaining clarity of insight and sharpening the intellect, one can perceive reality from its authentic perspective. Unlike the first extreme, which fuels passions, this Middle Way leads to the control of passions and ultimately to inner peace. Most importantly, it paves the way for achieving the four supramundane Paths of Sainthood, understanding the Four Noble Truths, and ultimately realizing the ultimate Goal, Nibbana.

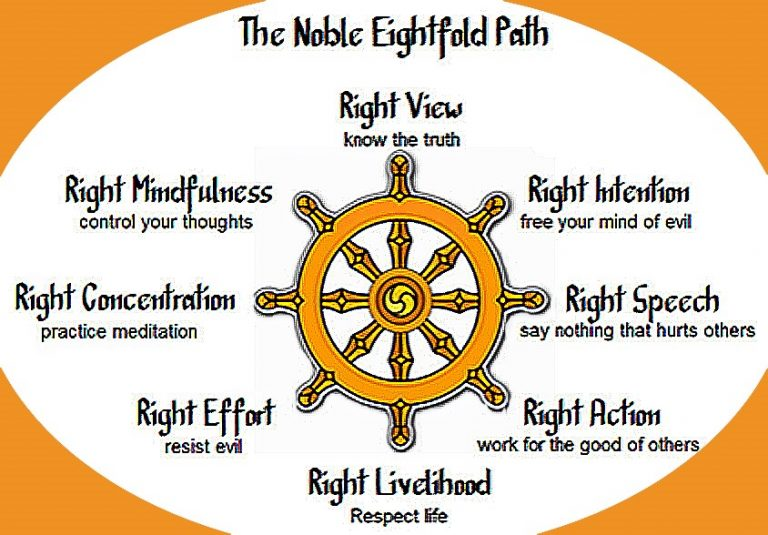

The Middle Way or the Noble Eightfold Path

The Middle Way or Middle Path, discovered by the Buddha, is commonly known as the Noble Eightfold Path due to its eight interconnected and esteemed components that are considered essential for attaining enlightenment. The term “noble” emphasizes the elevated nature of this path and underscores its profound importance in the pursuit of liberation from suffering.

In the discourse, these eight factors are systematically presented. The first factor is Right Understanding, which serves as the cornerstone of Buddhism. It involves gaining a deep knowledge of oneself as one truly exists. Right Understanding leads to Right Thoughts, encompassing renunciation, freedom from craving, goodwill, freedom from ill will, and harmlessness, free from cruelty. Right Thoughts, in turn, manifest as Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood, completing one’s moral conduct.

The sixth factor, Right Effort, focuses on eliminating unwholesome mental states and nurturing wholesome mental states within oneself. This process of self-purification is best facilitated through careful introspection, which necessitates the seventh factor, Right Mindfulness. Right Effort, when combined with Right Mindfulness, culminates in the eighth factor, Right Concentration, also known as one-pointedness of the mind. A mind that is focused and undistracted resembles a polished mirror, reflecting reality with utmost clarity and devoid of distortion.

By introducing the discourse with a discussion on the two extremes and presenting his newly-discovered Middle Way, the Buddha proceeds to expound upon the the Four Noble Truths in detail.

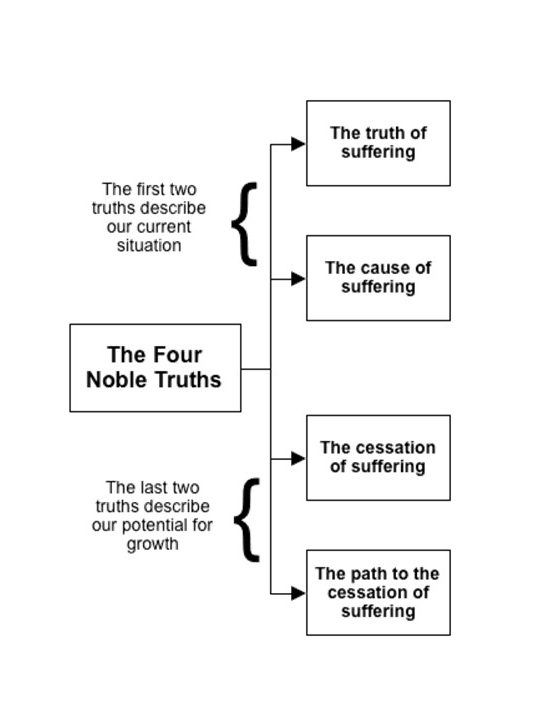

The Four Noble Truths[8]

Sacca, the Pali term for “Truth,” embodies the concept of “that which is,” while its Sanskrit equivalent, satya, represents an undeniable and factual reality. These truths are known as ariya saccani, meaning Noble Truths, in the Pali language. They are given this name because they were discovered by the Greatest Ariya, an individual completely removed from all defilements.[9]

These Truths exist regardless of whether a Buddha arises or not, and it is the Buddha who reveals them to a world engulfed in delusion. Being eternal in nature, they remain unchanging across time, as they are rooted in eternal truth. The Buddha, in this discourse, explicitly declares that his realization of these Truths was not indebted to anyone, stating, “With regard to things unheard before, there arose in me the eye, the knowledge, the wisdom, the insight, and the light.” These words hold great significance as they attest to the originality of his teachings.

The Buddha expounds four such Truths, which serve as the fundamental pillars of his teachings, as follows:

The first Noble Truth, dukkha-sacca, addresses dukkha, a term inadequately translated as “suffering” or “sorrow” in English. Dukkha, as a feeling, signifies that which is arduous to endure. As an abstract truth, dukkha conveys the notion of “contemptible (du-) emptiness (kha-).” The world rests upon suffering, making it contemptible. It lacks true reality, rendering it empty or void. Thus, dukkha can be understood as “contemptible void.”[10]

Ordinary individuals perceive only the surface of things. An Ariya, a Noble One, perceives reality as it truly is. To an Ariya, all life is unsatisfactory, and genuine happiness cannot be found in this deceptive world of illusory pleasures. Material happiness merely satisfies desires. Everyone is subject to birth and, consequently, to decay, disease, and ultimately death. No one is exempt from these four causes of suffering.

The absence of wish fulfillment is also a form of suffering. Generally, one dislikes being associated with individuals or things one dislikes, while desiring to be with those one favors. Moreover, cherished desires are not always fulfilled. Unexpected and unpleasant circumstances can become so intolerable and painful that weak and ignorant individuals may even consider suicide as a solution.

True happiness lies within and cannot be defined in terms of wealth, power, honors, or conquests. When such worldly possessions are acquired forcibly, unjustly, or are misdirected or attached to, they become sources of pain and sorrow for the possessors.

Typically, the pursuit of sensory pleasures represents the highest and sole form of happiness for the average person. Undoubtedly, there is momentary happiness in the anticipation, gratification, and recollection of such fleeting material pleasures, but they are illusory and temporary. According to the Buddha, greater happiness is found in non-attachment and transcending material pleasures.

The First Truth of suffering, which depends on this so-called “being” and various aspects of life, is to “be carefully perceived and examined”. This examination leads to a proper understanding of oneself as one really is.

The second Noble Truth, samudaya-sacca, addresses the origin of suffering. It teaches that all suffering stems from selfish craving (tanha in Pali) and ignorance.

There are three types of craving. The first is the most obvious form of craving, which involves attachment to sensory pleasures, the second is craving for existence and the third is craving for non-existence[11].

Craving is a potent, latent mental force present in everyone, and it serves as the primary

cause of many life’s afflictions. This craving, both gross and subtle, is found by the Buddha to lead to repeated births in the cycle of Samsara.

Right Understanding of the First Noble Truth paves the way for the “eradication” of

craving. Thus, the Second Noble Truth concerns the ordinary person’s mental disposition towards external objects of the senses.

The cause of suffering is craving or attachment. As stated in the Dhammapada (XVI,Affections, verse 216): “Craving brings grief; craving brings fear. For those who are free from craving, there is neither grief nor fear.”[12]

The Third Noble Truth, Nirodha-sacca, teaches that there is a complete cessation of suffering, which is Nibbana, the ultimate goal of Buddhism. It can be achieved in this life itself by the total eradication of all forms of craving.

The Third Noble Truth has to “be realized by developing the Noble Eightfold Path”. This unique Eightfold Path is the only way to reach Nibbana. This is the Fourth Noble Truth.

Expounding the Four Noble Truths in various ways, the Buddha concluded the discourse with the powerful words:

“As long, O Bhikkhus, as the absolute true intuitive knowledge regarding these Four Noble Truths,…, was not perfectly clear to me, so long did I not acknowledge,…, that I had gained the incomparable Supreme Enlightenment (Anuttara Samma-Sambodhi – Pali, or Anuttara-samyak-sambodhi – Sanskrit).”

“When the absolute true intuitive knowledge regarding these Truths,…, became perfectly clear to me, then only did I acknowledge,…, that I had gained the incomparable Supreme Enlightenment.”

“And there arose in me the knowledge and insight: ‘Unshakable is the deliverance of my mind, this is my last birth, and, now, there is no further becoming (birth) for me’.”

At the end of the discourse, Kondanya, the senior of the five disciples, realized that whatever is subject to origination is also subject to cessation and, thereupon, attained the first stage of Sainthood (Sotapanna).

Each factor of the Noble Eightfold Path contributes to the development and refinement of one’s ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom. They are considered interconnected and mutually supportive, working together to guide individuals toward the cessation of suffering and the realization of enlightenment.

The transformation of the First Sermon into the celebrated Asalha Puja, now also known as Dhamma Day.

As previously mentioned, Asalha Puja, also known as Asalha Bucha, holds significant importance as a Buddhist festival dedicated to honoring the Buddha’s inaugural sermon. This event marks a crucial turning point in the Buddha’s teachings and the establishment of the Buddhist Sangha, the community of monks.

During Asalha Puja Day, Buddhists engage in various religious activities such as visiting temples to engage in prayer, meditation, and listening to sermons. It is a time for deep reflection and a focused commitment to practicing the Dhamma. Devotees also offer their respects and make offerings at temples. For monks, this occasion signifies the beginning of a mandatory three-month Vassa Rains Retreat.

Asalha Puca Day was also recognized as Dhamma Day to honor and highlight the Buddha’s entire teachings as well.

How the Buddha taught 84,000 textual units!

According to The Pali Canon, What a Buddhist Must Know, p. 6, teachings of the Buddha consist of as many as 84,000 textual units. This figurative number represents the diverse aspects and approaches to spiritual development that the Buddha expounded. Here is a concise explanation of how the Buddha skillfully taught such a vast array of topics:

Adaptation: The Buddha employed skillful means to tailor his teachings to the needs and capacities of different individuals. He considered the varied inclinations, backgrounds, and levels of understanding of his disciples and imparted teachings accordingly.

Gradual Progress: Recognizing that people progress on the spiritual path at different paces, the Buddha provided teachings suitable for beginners, intermediate practitioners, and advanced students. This gradual path allowed individuals to develop their understanding and practice step by step.

Personal Guidance: The Buddha’s teachings extended beyond formal discourses and encompassed personalized guidance given to individual disciples. He tailored his instructions to address their specific needs, doubts, and challenges.

Versatile Methods: The Buddha employed diverse teaching methods and approaches to cater to the varied dispositions of his listeners. He utilized stories, parables, similes, direct instructions, contemplative practices, and philosophical discussions to effectively convey his teachings.

Emphasis on Core Principles: While addressing a wide range of topics, the Buddha placed particular emphasis on core principles underlying his teachings. These fundamental teachings include the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, the law of dependent origination, mindfulness, compassion, and the cultivation of wisdom.

Contextual Relevance: The Buddha taught within the context of specific situations, cultural backgrounds, and intellectual capacities of his audience. He often utilized examples and analogies that were relatable and meaningful to the people of his time.

Comprehensive Understanding: The Buddha’s teachings covered various dimensions of human existence, including ethics, meditation, wisdom, psychology, cosmology, and social harmony. He provided a comprehensive framework that encouraged his disciples to explore and understand the nature of reality from different perspectives.

Experiential Learning: The Buddha stressed the importance of personal experience and direct realization of truth. He encouraged his disciples to practice meditation, engage in ethical conduct, and cultivate mindfulness to develop their own understanding of the teachings.

The Buddha can be likened to a physician who diagnoses various types of illnesses, understands their causes, provides remedies, and knows how to apply them. Similarly, the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths, which encompass the nature of suffering, its origin, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation.

The Buddha’s Messengers of Truth and Compassion

After delivering the First Sermon to his five former spiritual companions, who had achieved enlightenment and understood the Four Noble Truths, the Buddha continued teaching and guiding additional disciples towards enlightenment. Within a few months, he successfully helped more individuals attain enlightenment. Once there were a total of 60 enlightened disciples who possessed a deep understanding of the Four Noble Truths, the Buddha decided to dispatch them to spread his teachings to all without distinction. Before dispatching them in the various directions, he exhorted them as follows:

“Freed am I, O Bhikkhus, from all bonds, whether divine or human. You,too, O Bhikkhus, are freed from all bonds, whether divine or human.”

“Go forth, O Bhikkhus, for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. Let not two of you go the same way: Teach, O Bhikkhus, the Dhamma, excellent in the beginning, excellent in the middle, excellent in the end, both in the spirit and in the letter. Proclaim the Holy Life, altogether perfect and pure.”

“There are beings with little dust in their eyes, who, not hearing the Dhamma, will perish. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.”

“I, too, O Bhikkhus, will go to Uruvela in Senanigama in order to teach the Dhamma.”

“Hoist the Flag of the Sage. Teach the Sublime Dhamma. Work for the good of others, you who have done your duty.”

A Take-home Message

On the occasion of Asalha Puja, we may contemplate the Four Noble Truths as the sublime truths discovered by the Buddha, which are true in all phenomena and aspects of Dharma. We also reflect on the Noble Eightfold Path as a means to extinguish the sorrows of the mind and as a tool for attaining the ultimate goal of the Buddha’s teachings. It remains the highest aspiration for Buddhists in living our lives.

To apply the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path in our daily lives in the present time is of utmost importance, as it brings numerous benefits. For example, it helps us solve various problems or overcome obstacles in life more effectively. Even while trying to solve problems or overcome obstacles, we may experience suffering, but it may not be excessive. This is because we approach problem-solving with a positive mindset, knowing that even though there are problems (suffering, Dukkha), we can find the causes of the problems (Samudaya), know that they can be resolved (Nirodha), and learn the methods and make sincere efforts to solve them (Magga).

I wish all readers happiness and well-being on the occasion of this year’s Dhamma Day.

ผู้เขียน : ดร. ไพฑูรย์ สงค์แก้ว

July 2023 (B.E. 2566)

References

Bomhard, Allan R. The Life of the Buddha, According to the Oldest Texts. Charleston Buddhist Fellowship, Charleston, SC USA. Revised August 2022.

Foucher, A. The Life of the Buddha: According to the Ancient Texts and Monuments of India. Translated into English by Simone Brangier Boas. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. First Indian Edition 2003.

Jootla, Susan Elbaum & Bomhard, Allan R. Transmitting the Dhamma. Charlston Buddhist Fellowship, Charleston, SC USA. 2019 (2563)

Malalasekera, G.P. Dictionary of Pali Proper Names, Vol. 1 A-DH. Motilal Banarsidas Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Delhi. 1960. (Entry: Kapilavatthu, pp. 516-520)

Payutto, Bhikkhu P.A. Buddhadhamma: The Law of Natures and Their Benefits to Life. 2015.

Payutto, Bhikkhu P.A. The Pali Canon: What a Buddhist Must Know. 2015.

Payutto, Bhikkhu P.A. Dictionary of Buddhism.

Thomas, Edward J. The Life of the Buddha as Legend and History. Motilal Banarsidass, Reprint: Delhi 1997, 2005, 2011.

Thich Nhat Hanh. Old Path White Clouds, Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha. Hin Pocket Book. 2017.

[1] Bamhard, Alland R. The Life of the Buddha. P. 27

[2] Allan R. Bomhard. The Life of the Buddha. P. 22.

[3] Craving is identified by the Buddha to lead to repeated births in the cycle of Samsara. This craving possesses a strong, dormant mental energy that exists within every individual.

[4] Robert Van de Weyer. 366 Readings from Buddhism. P. 5/26.

[5] See What Does Buddha Dharma Mean? Dhamma in Buddhism และ Buddhadhamma: The Law of Natures and Their Benefits to Life

[6] Types of liberation (Vimutti) in Theravada Buddhism

[7] It is crucial to note that the Buddha’s conversation took place specifically with the five ascetics who had been pursuing a path to spiritual liberation from suffering, rather than addressing ordinary individuals. It is important to avoid misunderstanding the Buddha’s intentions as expecting all his followers to renounce material pleasures and withdraw from the world, leading a joyless existence. His perspective was not so narrow. While discussing worldly happiness, the Buddha acknowledged that acquiring wealth and enjoying possessions can bring pleasure to laypeople. However, an enlightened recluse, possessing wisdom, would not seek fulfillment solely through the pursuit of these temporary pleasures. It may surprise the average person that a recluse might actually choose to avoid them.

[8] What Are the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism?

[9] Bomhard, Allan R. The Life of the Buddha. P. 51.

[10] Bomhard, Allan R. The Life of the Buddha. P. 51.