The Change in Women’s Opportunities in Buddhism

By laying out the basic doctrine of Buddhism that salvation is by one’s own effort, the Buddha suggested that the highest spiritual states were within reach of women, not just men.

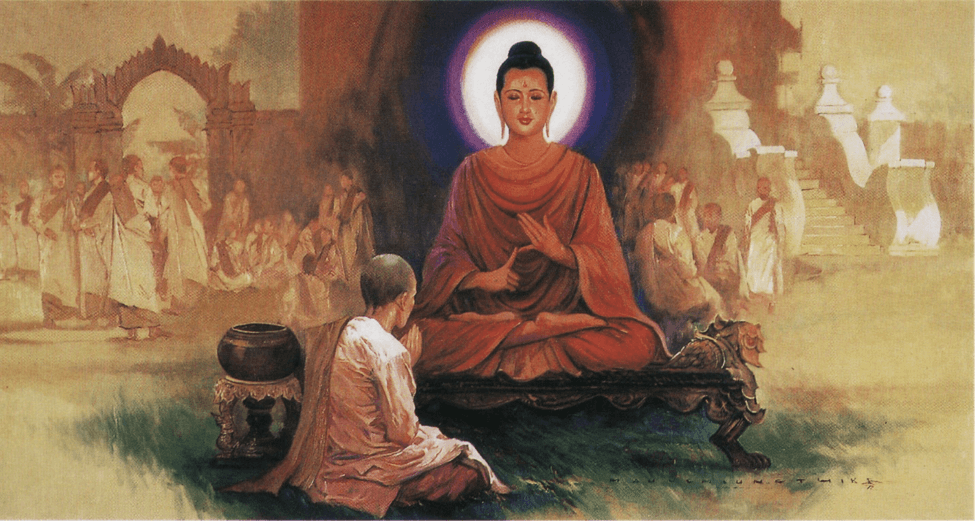

Maha Pajapati Gotami requesting for permission from the Buddha to establish the monastic Order of Nuns (Bhikkhuni Order) (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3hmleq4)

Maha Pajapati Gotami requesting for permission from the Buddha to establish the monastic Order of Nuns (Bhikkhuni Order) (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3hmleq4)

International Women’s Day 2022 is celebrated on March 8. Its theme is “Gender equality today for a sustainable tomorrow,” and it recognizes the contribution of women and girls around the world. On this occasion, I would like to join the world in honoring women, particularly from a Buddhist perspective.

About 2,000 to 3,000 years ago, there was probably no concept of ‘gender equality’ in the world. The prevailing idea was that men were super, stronger, and more capable than women. In many cultures, men had authority over women because men claimed that gods had made them more superior. That mentality still lasts today, when women in some societies are still not allowed to study, sometimes due to misinterpretations of religious creeds.

Fortunately, the nineteenth-century movements of the West have influenced various corners of the world to think about women’s roles differently, unlike the world in which the Buddha was born.

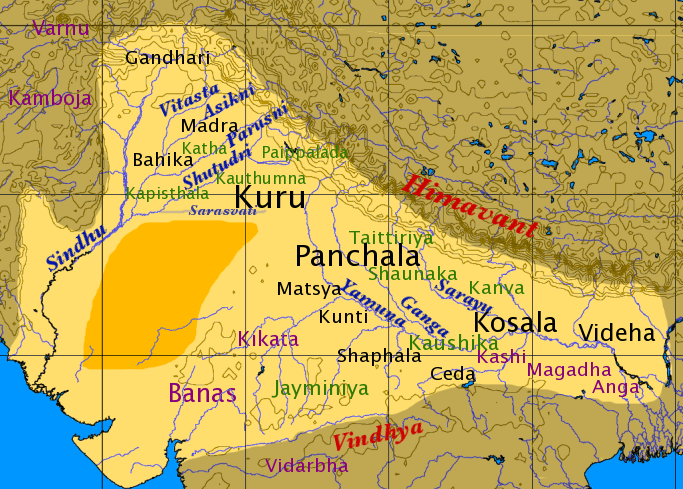

In the Vedic land where the Buddha was born, and at first known as Siddhattha Gotama, although there were some customs to honor women, they were still relatively mistreated. The great Indian historian R.C. Majumdar described the social conditions for women in India during the Vedic period as a devolvement from the previous era. Whereas wives had earlier been accorded a somewhat high position, considered the other half of her husband, their status and dignity were lowered a great deal during the late Vedic period. Many religious ceremonies, previously under the wife’s duties, became performed by male priests, and wives saw greater limitations. for instance, wives were not allowed to attend political assemblies; a submissive, quiet wife who dined after her husband was held up as the ideal; births of daughter became unwelcome, for they were regarded as a source of misery, and only sons were seen as saviors; the Laws of Manu (circa 500 BC) considered women inept, inconsistent, and sensual; women were restrained from learning Vedic texts or participating in meaningful social functions and kept in abject subjugation all their lives.

Map of Vedic India in light yellow (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3LPL57B)

Map of Vedic India in light yellow (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3LPL57B)

Against this background the Buddha emerged. The Buddha, whose original name was Siddhattha Gotama (or Siddhartha Goutama), was born to a royal family that ruled a small city state in modern-day Nepal, near the border of India, in the late 6th century B.C.E. Siddhattha renounced his royal, worldly life to become an ascetic at the age of 29, becoming enlightened at the age of 35 after which he spent the rest of his life teaching Buddhism in what is now the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh until he passed away at 80 years old. During his lifetime, he changed what women’s possibilities were in Buddhism and therefore in his society.

A temple is built over the spot believed to be the birthplace of the Buddha at Lumbini, Nepal.

A temple is built over the spot believed to be the birthplace of the Buddha at Lumbini, Nepal.

(Photo by the courtesy of the Embassy of Nepal in Bangkok)

Map of the places in Northeastern India where the Buddha spent his life

Map of the places in Northeastern India where the Buddha spent his life

(photo credit: https://bit.ly/3rF5Kn2)

The Buddha’s Contribution to Women’s Status

When the Buddha was about 40 years old—five years after the establishment of the Order of Monks (bhikkhu in Pali)—his father Suddhodana passed away. His foster mother, Maha Pajapati Gotami, fell into a deep loneliness. Siddharta, now the Buddha, had renounced worldly living eleven years prior, and his half-brother, Nanda, had also joined the Order of Monks a year before Suddhodana’s death.

Since she was already a strong lay follower of Buddhism (sotapanna in Pali), Maha Pajapati Gotami wished to join the Buddhist community as a nun; however, such an option did not yet exist. Men’s opportunities to become priests were not mirrored.

Along with other women, Maha Pajapati Gotami asked the Buddha for permission to become a nun (when the Buddha visited Kapilavatthu to settle the dispute between the Sakyans and the Koliyans over the right to water from the Rohini River). The Buddha initially refused, perhaps succumbing to societal pressures that women should not have such opportunities, and went on to Vesali (modern-day Vaishali) not granting Maha Pajapati her wish.

However, Maha Pajapati and her companions, undaunted, insisted in creative and persistent ways. They asked barbers to cut off their hair and donned yellow robes, following the Buddha to Vesali on foot for all 250 kilometers. They arrived at the Buddha’s monastery with wounded feet. There, they met with Venerable Ananda, who was the first cousin and close companion of the Buddha. Ananda was astonished to see his aunt Maha Pajapati Gotami in such a sorry state. She told him the purpose of her mission, and he interceded, entreating the Buddha three times, always meeting resistance.

Finally, Ananda tried to reason by asking the Buddha whether it was not possible for a woman to attain the bliss of sainthood (arahant in Pali). The Buddha, responding to this, replied that a woman could attain sainthood, like a man, and consented to the establishment of the Order for Nuns. However, he issued conditions: a nun, even if she had been in the Order for 100 years, for instance, must show respect to a monk of only a day’s standing; a nun, he also demanded, should reside within six hours of travelling distance to and from the monastery where monks, who presumably would give them advice, would reside. When Venerable Ananda relayed the news to Maha Pajapati Gotami, she gladly accepted the conditions. She and her companions became nuns, known as bikkhuni, and learned meditation from the Buddha, achieving Arahant status soon afterwards.

The pillar of Ashoka at the ruin of an ancient Buddhist complex at Vesali (or Vaishali) where the Buddha granted Maha Pajapati Gotami the ability to become a nun and establish the Order for Nuns in Buddhism. (Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3t7E61x)

The pillar of Ashoka at the ruin of an ancient Buddhist complex at Vesali (or Vaishali) where the Buddha granted Maha Pajapati Gotami the ability to become a nun and establish the Order for Nuns in Buddhism. (Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3t7E61x)

Although the Buddha did not inaugurate a campaign for the liberation of women, he implicitly uplifted women’s status. By laying out the basic doctrine of Buddhism that salvation is by one’s own effort, he suggested that the highest spiritual states were within reach of both men and women, and that the latter needed no masculine assistance or priestly intermediary for their practice. In the context of his times, the Buddha was a man of considerable courage and a rebellious spirit, pronouncing a way of life that placed women on a level of greater equality to men.

Women in Buddhism in the modern world

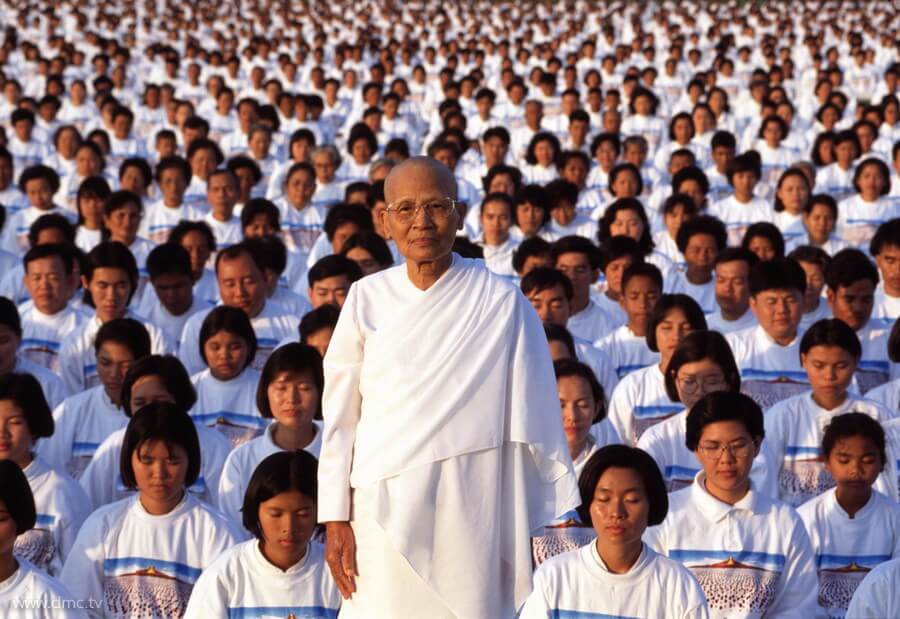

The Order of Nuns became one of the earliest organizations for women. The Bhikkhuni Order continues until today. However, in most countries where Theravada Buddhism is prevalent, including Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand, the Order of Buddhist Nuns has never been a legal entity. Instead, there are a group of Buddhist women who commit to Buddhism’s core precepts, wear white robes, and shave their heads, serving as nuns, but not being fully ordained bhikkhuni. They are called donchee in Cambodia, maekhao in Laos, thila shin in Myanmar, and Mae-chi in Thailand. They live and study in a convent.

Buddhist nuns of Sri Lanka (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3vnubHG)

Buddhist nuns of Sri Lanka (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3vnubHG)

Myanmar thila shin or nuns (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3spdx8C)

Myanmar thila shin or nuns (photo credit: https://bit.ly/3spdx8C)

Mae chi Chandra Khonnokyoong who founded Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Thailand

Mae chi Chandra Khonnokyoong who founded Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Thailand

(photo credit: https://bit.ly/35cl7e0)

There is also the Order of Mahayanist Nuns in China, Japan, South Korea, and Malaysia.

Taiwanese Buddhist nuns (photo credit: https://yhoo.it/3hthXVH)

Taiwanese Buddhist nuns (photo credit: https://yhoo.it/3hthXVH)

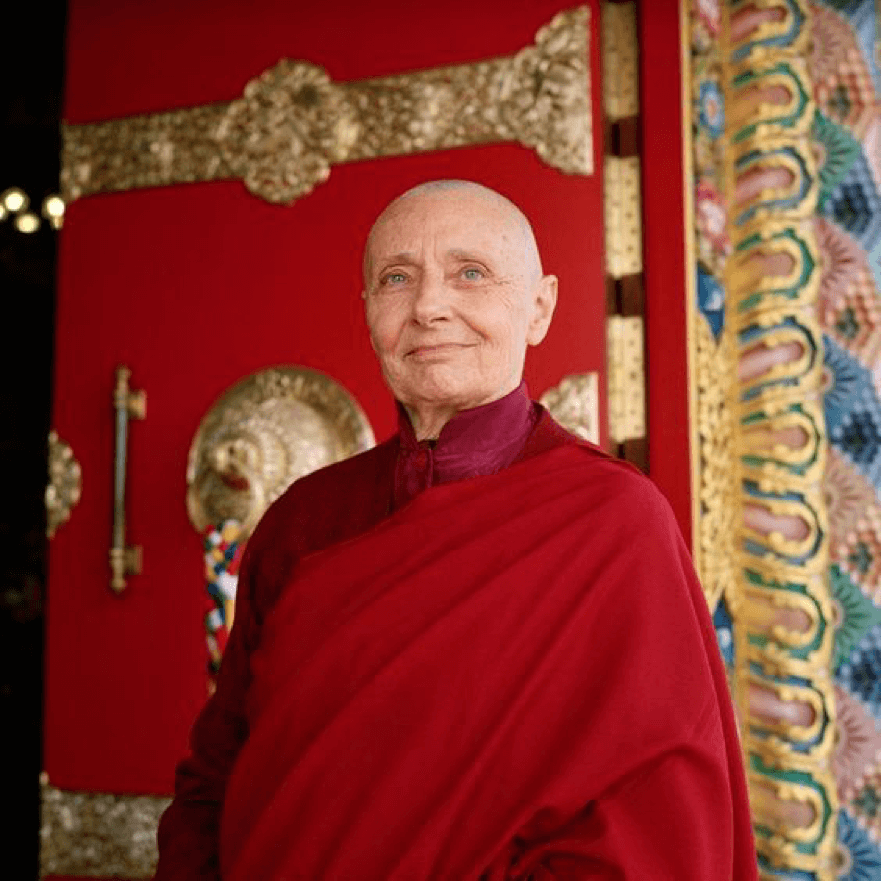

Nun Tenzin Palmo says there is nothing a woman can’t accomplish.

Nun Tenzin Palmo says there is nothing a woman can’t accomplish.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3t9RmTf)

In addition to allowing women to become nuns, the Buddha’s treatment of women also helped alleviate the suffering of women in patriarchal societies by decreasing the perceived need to have a son, a need that arose sometimes due to customs of funeral rites. In the case of Hindu society, for instance, funeral rites are particularly male-centered: only a son can carry out the funeral rites for his father, i.e. ensure the happiness of the deceased; daughters are not considered to have this capacity. In Buddhism, on the other hand, funeral rites do not ensure happiness of the deceased; the actions of the deceased before their death determines what happens after death. The Buddhist funeral ceremony is a very simple one which can be performed by a widow, a daughter, and even a stranger; the presence of a son is not compulsory. It is well known that the Buddha consoled King Pasenadi, who came to him grieving that his queen, Mallika, had given birth to a daughter, by saying, “A female offspring, O’ king, may prove even nobler than a male…” which was a revolutionary statement for his time.

Lastly, the Buddha laid down (in the Sigalovada Sutta) the duties of a husband and wife: that a husband has five duties toward his wife, namely respect, courtesy, faithfulness, handing over domestic authority to her, and providing her with ornaments. In return, the wife has five duties toward her husband, namely being faithful, managing household affairs well, being hospitable and helpful to friends and relations, taking care of the goods he brings home, and being skillful and industrious in all her duties. Such clarity of duties towards wives helped to remind men of the values they owed their wives.

On International Women’s Day 2022, I wish for greater gender equality and for the well-being of women and girls around the world.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3BXaZlk)

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3BXaZlk)

Main sources:

- Majumdar, R.C. Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 2013.

- The Position of Women in Buddhism by Dr. (Mrs.) L.S. Dewaraja at https://bit.ly/34azIq3

- What does the Koran say about women? at https://bit.ly/35L0pSu

- Harris, Ian. The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Buddhism.

Author: Paitoon Songkaeo, Ph.D.

5 March 2022