Disclaimer: This is an article on Buddhism, a major global religion and system of beliefs with a complex history of more than 2,600 years. It is written to the best of the author’s knowledge. The intention of this article is to introduce Buddhism to readers, particularly in regards to its

founder, history, doctrines, and usefulness through meditation. Many hyperlinks and reference video clips are suggested under each section in order to facilitate the readers’ further exploration of the Buddhist world and to allow them to reap the benefits of meditation. There is by no means an intention for this article alone to cover all subjects of Buddhism exhaustively.

Note on the Pali terms used in the article: Originally, the Buddha’s Teachings were recorded in the Pali language. English translations of these terms sometimes vary. The author therefore finds it necessary to occasionally recall these original terms in parentheses, so that the readers may have reference to the original term where it may be useful. The author is extremely grateful to Phra Thepsakyawongpundit (Anilman Dhammasakiyo) for some comments.

Introduction

The word Buddhism is the Western term for the teachings of the Buddha or the religion founded by the Buddha. Western scholars coined the term in early 19th century to refer to their newly discovered complex of religious practices centered on the image and memory of the figure called the Buddha, the Enlightened One. Early Buddhists, in fact, used such alternative terms as Dharma “doctrine” or Dharma Vinaya, “doctrine-disciplines”, to refer to this belief system. In Sanskrit sources, these often became the Buddha Dharma, the “doctrines of the Buddha.” The word Boudhism was introduced in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1801 and emerged as Buddhism in 1816.

Read more : Buddhism by country

What is Buddhism?

Understanding “Buddhism” and “The Buddha”

“Buddhism” is the English term for the teachings of the Buddha (see hyperlink p. 4), or the religion founded by the Buddha, who was known – among a few variations – as Siddhattha (or Siddhartha) Gotama before he reached the final stage of enlightenment (Pali: bodhi), which allowed him to reach spiritual release (nibbana or nirvana). Western scholars coined the term “Buddhism” in the early-nineteenth century to refer to their discovery of a complex set of religious practices centered on the image and memory of a figure called “the Buddha.” The word “Buddhism” was introduced in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1816. [1]

In Thailand, Buddhism is known as “Buddha-sasana,” which translates as “the Buddhist religion.” Buddha-sasana is a Pali-derived term, which is also used in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka, where Buddhism is the dominant religion as well.

Earlier Buddhists had used alternative phrasings to describe Buddhism, such as “Dhamma or Dharma” or “Buddha Dharma” – both meaning “the doctrines of the Buddha” – or “Dhamma Vinaya” – meaning “doctrine-disciplines” – to refer to what is currently called “Buddhism.”

Buddhism is a religion of action and of effort, not a religion of supplication. The Buddha said as quoted in Buddhadhamma’s chapter 5: Kamma (see details pp. 310 – 428):

“All accumulated deeds, both good and bad, bear fruit. Actions marked as Kamma, even trifling ones, are not void of result.”

“Neither good or bad deeds are performed in vain.”

“The meritorious deeds one has done – that is one’s friend in the future.”

“Whatever sort of seed is sown, that is the sort of fruit one reaps: The doer of good reaps good; the doer of evil reaps evil.”

As for supplication, the Buddha said, “…And I say that these five things – long life, beauty, happiness, fame, and heaven – are not got by praying or wishing for them. If they were, who would lack them?… They should practice the way that leads to long life…. For by practicing that way they gain long life….”

Read more : You don’t get good things by praying for them, but by how you live.

The word “Buddha” means “the Awakened One” or “the Enlightened One” (see hyperlink p. 22), and it is not a name. As a person, the Buddha lived more than 25 centuries ago as Siddhattha Gotama before he reached enlightenment. He was born in modern-day Nepal as a prince to a royal family of the Sakyan Kingdom, of which the capital was Kapilavatthu (or Kapilavastu), located at the foot of the Himalayas. His father, who was the king ruling over the Sakyas, was Suddhodana. The queen, who was the prince’s mother, was Maya. He married princess Yasodhara or Bimbadevi or Gopa, his cousin of the same age, who bore him a son, Rahula [2] at the age of 29.

Read more : The Old Path White Clouds, chapter six – Beneath a Rose-Apple Tree – which is about the birth of Prince Siddhartha

Since childhood, Siddhattha was very compassionate. As a clever prince, he studied all subjects that a prince should learn in order to become a good ruler. In addition, he learned major scriptures in Brahmanism/Hinduism, which were taught at that time, such as the Four Vedas, the Six Vedangas, and the Upanishads.[3] He was particularly fascinated with the doctrines of samsara (rebirth or reincarnation), moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and death), and Atman (self) in the Upanishads.

Understanding the Buddha’s Quest for Truth

In Buddhism, unenlightened humans live in a state comparable to sleep or a dream. Through the clear light of wisdom, the Buddha awoke from that dream, arriving at the true nature of existence, which he compassionately wanted to share, in order to set others also on the path to awakening or enlightenment.

To understand Buddhism, one first has to understand a few prior concepts, as well as the story of how Siddhattha interacted with these concepts, mostly originally from Brahmanism/Hinduism.

The first concept is samsara. Samsara is the concept of rebirth, reincarnation, or transmigration of the soul in Brahmanism/Hinduism. According to this concept, the soul may occupy a range of bodies, from plants to animals and humans, though it always remains untouched, eternal, and pure.[4] (Reincarnation picture credit).

The second concept is moksha, meaning liberation or release from the cycle of birth and death. It implies union with the One Reality (Brahman), where individuality disappears.

The third concept is Atman (also sometimes known as Atma). It is a Sanskrit term for the self or soul, which is imperishable and eternal. In the Rig Veda, the term means “breath” or “vital essence.” (The concept of Atman is developed in the Upanishads.) The Atman is not the same as the body, the mind, or consciousness, but it is something beyond that permeates all these. In some passages of the Upanishads, the Atman is considered identical to Brahman, the underlying reality of the world, and thus there is only one Atman that permeates all beings.[5]

Wanting his son to be king, Siddhattha’s father tried to keep the prince’s mind attached to the world and satisfied with the enjoyment of the sensual pleasures; however, as predicted by a family sage, the prince’s mind was more preoccupied with a desire to solve the problem of samsara: How can one liberate oneself from the circle of birth or rebirth, which involves death again and again, and how can one help other people to be free from samsara?

Enthusiastically, at the age of 29, Siddhattha asked for his wife’s and father’s permission to leave his family and the palace. He told his wife, “…though I will be gone, though I will be far away from you, my love for you will remain the same. I will never stop loving you… And when I have found the Way – the answer to his question -, I will return to you and to our child.”[6] He also promised his father, “I will never abandon you. I am only asking you to let me go away for a time. When I have found the Way, I will return.”[7] (The word “Way” used above – meaning path, road, or step – is a translation of the Pali word “Magga”. It signifies a particular way leading to a particular goal, such as salvation, bliss, knowledge, or pleasure. The term is also used as an equivalence of “method,” or a means for reaching certain ends, generally in consonance with Dhamma.

Siddhattha then left his family and became a wandering religious mendicant (Pali: paribbajaka) in order to find the Way. After six years of studies, including an experiment in the forest inspired by Brahmani ascetism – which he had hypothesized was key – Siddhattha realized that asceticism was also not the answer. He gave up ascetic practices, intending for a rational, simple life of moderation instead.

Read more: The Old Path White Clouds, Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha’s Chapter twelve – Kanthaka, which is about the conversation between prince Siddhartha and his wife and his father before his departure, Chapter thirteen – Beginning Spiritual Practice, and Chapter fifteen – Forest Ascetic

The Pipal (or peepal, or pippala) tree would later become known as Bodhi Tree by virtue of the Buddha’s enlightenment. The tree is traditionally hailed in Indian subcontinent as the tree of life, for it generously yields products beneficial to health and beauty.[8]

On the night of the full moon in the month of May, forty-five years before the Buddhist Era, Siddhattha, sitting under a peepal tree underwent great progress in his search, and an omniscient illumination came over him. In that night, under the tree, he achieved enlightenment, finally understanding the origins of the suffering and reincarnation. He said, as quoted in Dr. Hermann Oldenberg’s Buddha; his Life, his Doctrine, his Order {(translated from the German by William Hoey (see hyperlink p. 107)}, “When I apprehended this, and when I beheld this, my soul was released from the evil of desire, released from the evil of earthly existence, released from the evil of error, released from the evil of ignorance. In the released awoke the knowledge of release: extinct is re-birth, finished the sacred course, duty done, no more shall I return to this world; this I knew.”

The Bodhi Tree received its new name for the meaning of “bodhi” – knowledge, wisdom, enlightenment. Where it is, in present-day Gaya District, Bihar State, India, later became known as Buddha Gaya, now also spelled Bodh Gaya or Bodhgaya.

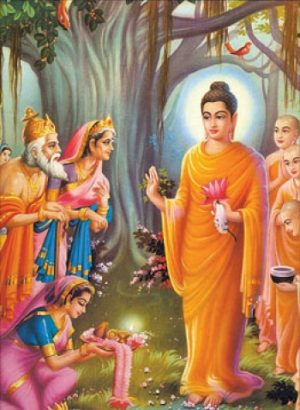

Now enlightened and known as “the Buddha” at the age of 35, the Buddha went from Gaya to modern-day Sarnath, near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, where he preached his first sermon. Then, a year later, the Buddha returned to his hometown, Kapilavatthu, to see his family as he had promised.

A stupa in Bodh Gaya was built to mark the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment in Bihar, India. This holy place is called Mahabodhi Temple, or Temple of the Great Enlightenment, or Mahabodhi Mahavihara, or Monastery of the Great Enlightenment, in today’s discourse.

For the next forty-five years of his life, from the ages of 35 to 80, the Buddha would travel from place to place to teach all who would listen. He organized his followers, who similarly renounced the material world, to form the Sangha.

Read more : The Old Path White Clouds…, chapters twenty-one – The Lotus Pond, and leaf, and twenty-two – Turning the Wheel of Dharma

Read more : Buddha’s first sermon, Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion

At the age of 80, however, the Buddha fell ill while on his way to Kusinara (modern-day Kushinagar), capital of the ancient Malla State.

P. A. Payutto (Somdej Phra Buddhaghosacariya), a revered monk, writes in the book Thai Buddhism in the Buddhist World, (see hyperlink p. 6), “In his deathbed under two Sal trees in the Sal Grove of the Mallas, he told his disciples that they would not be left without the Teacher: ‘The Doctrine and Discipline I have taught you, that shall be your teacher, when I am gone… Behold now, monks, I exhort you. Subject to decay are all component things. Work out your salvation with diligence.’”

A stupa was built to mark the place of the Buddha’s passing away (Pali: Maha-parinibbana, which means the Great Demise) at Kushinagar in Uttar Pradesh State (Pictured Below)

Read more : Maha-parinibbana Sutta: Last Days of the Buddha.

Read more : The Buddha, His Life and Teaching

Read more : The Life of Buddha, as Legend and History.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJf4ivzOcS4

(On the Path of the Buddha: Buddhist Pilgrimage in North India and Nepal)

Understanding Dhamma, or Dharma

The Buddha’s teachings are known as Dhamma in Pali or Dharma in Sanskrit. Since the Dhamma is taught by the Buddha, it is known as Buddha-Dhamma or Buddhadhamma. It includes many beliefs that were popular in 5th century BCE India, and the Buddha’s own discoveries. For example, the Buddha acknowledged the Bharmanical-Hindu pantheon of gods, devas and other supernatural entities. He confirmed the belief in Samsara, or reincarnation, or rebirth saying that upon his enlightenment, he remembered his many previous lives. As for his own’s discoveries, apart from rejecting the concept of Atman, saying that in absolute truth (Pali: Paramattha-sacca) there is no self, or soul (Pali: anatta), he taught the Four Noble Truths, which is about the nature of reality, the Noble Eightfold Path, which can lead to self-transformation and enlightenment, the Dependent Origination (Pali: pathiccasamuppada), and Nibbana.

The Buddha used many different methods when teaching Dhamma, so that everyone may benefit. His teachings contain many layers, separable into those aimed for householders and members of mainstream society, and those aimed for individuals who have relinquished domestic life. There are teachings focused on material benefits and others focused on deeper spiritual benefits. The Buddha said that his teachings are something to be experienced, not unquestioningly believed, especially anatta, the Dependent Origination, and nibbana. This idea has been explained in various iterations, including:

“This doctrine is profound, hard to see, difficult to understand, calm,

sublime, not within the sphere of logic, subtle, to be understood by the wise.”

“Well expounded is the Dharma by the Blessed One, to be self-realized,

with immediate fruit, inviting investigation, leading onwards, to be comprehended by the wise, each by himself.”

“You yourselves must make the effort. The Buddha only points out the

Way.”

“Seeing one’s own good, let him work it out with diligence. Seeing the good

of others, let him work it out with diligence. Seeing the good of both, let him work it out with diligence.”

Read more : Rebirth in the book Buddhadhamma, pp. 365-367 Karma and Rebirth

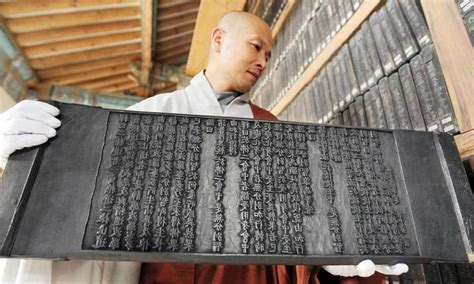

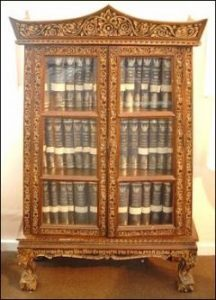

The Buddha’s teachings are preserved in scriptures called Tipitaka in Pali or Tripitaka in Sanskrit. The Tipitaka contains three parts or “baskets” of teachings: Vinaya Pitaka (“The Basket of Discipline”), Sutta Pitaka (“The Basket of Discourse”), and Abhidharma Pitaka (“The Basket of Analytic Doctrine”).[9] Vinaya is the set of rules and regulations for monastic life, which range from dress code and dietary rules to rules against certain personal conducts. Suttas, also commonly known as Sutras in Sanskrit, are the doctrinal teachings in aphoristic or narrative format. (All of the Buddha’s sermons were rehearsed orally during the meeting of the First Buddhist council just three months after the Buddha’s death. The Buddha’s teachings continued to be transmitted orally until they were written down in books in modern-day Sri Lanka in the first century BCE.) Abhidhamma is the philosophical and psychological analysis and interpretation of Buddhist doctrine.

The Tipitaka is preserved in different forms, as shown in the images below :

Two months after his enlightenment at Bodh Gaya, the Buddha talked for the first time about his discovery of the Way. This sermon is recorded in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (translated as “The Discourse on Setting in Motion the Wheel of Dhamma”) to five former spiritual companions at modern-day Sarnath, India. Some basic teachings are contained in the statements known as the Four Noble Truths, sometimes known as the Middle Way. These, too, should be understood in detail to understand the Buddha’s teachings.

(The ancient stupa, pictured below, with Thai pilgrims, was erected to mark the place of the Buddha’s first sermon. Photo credit: a Thai Buddhist monk in India)

First, there is the Noble Truth of Suffering (Pali: dukkha), which dictates that all the problems of life—from birth to death, including sorrows, illnesses, and frustrations of every kind—are things that people try to avoid; however, like everything else, these problems are transient and lacking in an underlying enduring substance. They can cause sorrow and frustration to anyone who clings onto them. Those who want to avoid and be free from suffering must approach life with the right attitude, knowledge, and wisdom, seeing things as they are.

Second, there is the Noble Truth of the Origin of Sufferings (Pali: dukkha-samudaya), which teaches that suffering arises through various causes and conditions, all tied together as cravings or selfish desires rooted in ignorance. Not recognizing things as they are, people crave for and slavishly cling to sensual pleasures, existence, and even self-annihilation. Through these, they perform various evil actions with the body, speech, and mind, resulting in their own suffering and the suffering of others, prompting a vicious cycle, if unstopped.

Third, there is the Noble Truth of the Extinction of Suffering (Pali: dukkha-nirodha), which teaches that when ignorance is completely destroyed or selfish desire is eradicated and replaced by the right attitude of love and wisdom, nirvana will be realized. Even for those who have not completely destroyed ignorance and craving, they can still make progress towards less suffering when they lessen their desires. The more their life is guided by love, wisdom, knowledge and compassion, the more their life will be happy, for themselves and those surrounding them.

Lastly, there is the Noble Truth of the Path Leading to the Extinction of Suffering (Pali: Dukkha-nirodhagamini patipada). This Truth defines the Buddhist way of life and provides the way to attain the goal of the Third Truth. This way is called the Noble Eightfold Path, as it consists of eight factors, namely: The Right View (Pali: sammaditthi), The Right Thought (Pali: sammasankappa), The Right Speech (Pali: sammavaca), The Right Action (Pali: sammakammanta), The Right Livelihood (Pali: samma-ajiva), The Right Effort (Pali: sammavayama), The Right Mindfulness (Pali: sammasati), and The Right Concentration (Pali: sammasamadhi). These essentially correspond to three fundamental principles: to not to do evil, to cultivate a good conscience, and to purify the mind. Those who follow the Four Noble Truths (Pali: ariyasacca) avoid the two extremes of sensual indulgence and self-annihilation, living a balanced life in which material welfare and spiritual well-being complement each other.

Understanding the Buddha as a “Physician”

Some have compared the method of the Buddha to that of a physician, as he made a “diagnosis” of the disease (suffering), understood its cause, predicted its outcome, and prescribed its cure. It is for this reason that the Buddha called himself a physician. He has also been compared to a surgeon who can remove the arrow of sorrow.

As medicine deals with diseases and cures, the Buddha’s teaching deals with suffering and the end of suffering. And as the process of medical treatment includes the prevention of disease by promoting and maintaining good health, the Buddhist process includes the promotion of mental help to guide one towards bliss or even reach enlightenment.

Read more : The Basic Teachings of Buddhism, pp. 7-12

Read more : Unit 2: Basic Teachings of the Buddha in Following the Buddha’s Footsteps

Understanding Audience-Specific Teachings

In the forty-five years during which he would teach the ideas of Buddhism, the Buddha talked to people from all walks of life, be it youth, adults, the old, people on a deathbed, an emperor, a king, a governor, a government official, ordinary people, the untouchables, men, women, the rich, the poor, farmers, soldiers, law enforcers, law breakers, monks, or even his religious rivals. In the Buddhist lens, all humans are equal.

Although it has now been more than 2550 years since the death of the Buddha, his teachings remain our teacher as he himself had intended for them to be. Each teaching should be studied in its own light and spirit, as some teachings are intended for monks, others for lay devotees, and some for both.

For example, the Buddha preached his first and second sermons to ascetics, who were his old spiritual companions seeking enlightenment. These five companions were striding on the traditional paths to liberation that is on sensual happiness and self-torture. As aforementioned, the Buddha had tried extreme paths and found that they were not the correct ways to enlightenment. With them, he shared the Middle Way (Pali: Majjhimapatipada), which he had just discovered under the Bodhi Tree.

Read more : Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta, translated from the Pali: by Bhikkhu Bodhi

Read more : Middle Way

Read more : The Buddhist Concept of Impermanence

Read more : Dependent Origination

Read more : The Four Noble Truths

The Buddha’s second sermon, Anattalakkhana Sutta (The Discourse on the Characteristic of No-Self) is for monks to follow. The Buddha preached this sutta to the same group of five ascetics who only a few days earlier were listening to his first sermon. In this discourse, the Buddha said that he had searched but could find no evidence for the existence of an eternal soul or a creator god. He conceived of the world and all of its elements as made up of components or qualities. He believed that humans are merely composed of five groups of components known as khandhas, which are: corporeality (Pali: Rupa-khandha); feeling (Pali: Vedana-khandha); perception (Pali: Sanna-khandha); mental formations or volitional activities (Pali: Sankhara-khandha), and consciousness (Pali: Vinnana-khandha). He refuted the earlier concept of Atman by analyzing the khandhas, demonstrating that they are each impermanent (Pali: anicca), subject to suffering (Pali: dukkha) and thus unfit for identification with a “self” (Pali: atta or Sanskrit: atman). In short, there is no self (atta, or atman). The Buddha said:

Bhikkhus, form is not-self. Were form self, then this form would not lead to

affliction, and one could have it of form: ‘Let my form be thus, let my form be not thus.’ And since form is not-self, so it leads to affliction, and none can have it of form: ‘Let my form be thus, let my form be not thus.’

Bhikkhus, feeling is not-self…

Bhikkhus, perception is not-self…

Bhikkhus, determinations are not-self…

Bhikkhus, consciousness is not self. Were consciousness self, then this consciousness would not lead to affliction, and one could have it of consciousness: ‘Let my consciousness be thus, let my consciousness be not thus.’ And since consciousness is not-self, so it leads to affliction, and none can have it of consciousness: ‘Let my consciousness be thus, let my consciousness be not thus.’…

For nuns and monks, too, the Buddha had specific teachings, such as the following:

“A monk should guard all the doors of the senses, for only by guarding the

doors of the senses can he obtain release from all suffering.”

“It is good to be disciplined in body. It is good to be disciplined in words. It is

good to be disciplined in mind. The monk who is disciplined in all these areas will achieve freedom from all suffering.”

“Surrounded by craving, the masses tremble like a hare caught in a trap.

Therefore, a monk desiring to attain detachment – nirvana – should shun craving.”

“Do not indulge in heedlessness. Avoid craving for sensual pleasures,

whatever their nature. The mindful person is tranquil in mind. He will attain great bliss.”

“Practice of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment (Pali: Bojjhanga) and non-

attachment (Pali: Anupadana) ensures nirvana.”

Read more : Anattalakkhana Sutta

Read more : Anatta-lakkhana Sutta: The Discourse on the Not-self Characteristic, translated from the Pali

The Buddha also taught laymen lessons. For example, he taught a young householder, Sigala, as recorded in Sigalovada Sutta, the fourteen evils that a layman should avoid. The fuller story goes: One day, after a morning bath, Sigala was worshiping the Six Directions or Quarters (Pali: Disa) – east, south, west, north, below, and above – as his father had told him to do before the latter’s death. While Sigala was performing his worship, the Buddha approached Sigala and talked in length with him on how to rightly worship the six quarters. That is: they are not merely directions, but the true “six quarters” in life should be parents, teachers, spouses, friends and colleagues, monks, and servants. He elaborated on how to respect and support them, and how in turn the Six Directions will return the kindness and support. Moreover, he explains that a layman should not take life, steal, engage in sexual misconduct, or lie. Laymen should avoid the four causes of evil actions: sensual desires, hate, ignorance, and fear. And as householders, in particular, they should avoid the six ways of squandering wealth: indulging in intoxicants, wandering questionable streets, frequenting public spectacles, gambling, befriending questionable people, and idling. The Buddha then elaborated on the importance of having and being a true friend, as he described what true friends are and what true friends are not, and how true friends are crucial in attaining a blissful life.

Read more : Sigalovada in Pictures

Read more : Dighajanu Sutta (Buddhist lay ethics)

There are many discourses which are meant for monks, nuns, and followers regardless of gender, such as the Mangala Sutta. Mangala, a Pali term, can be translated as ‘blessings,’ ‘good omen’, ‘auspice,’ ‘good fortune’, and ‘greatest happiness’. Specifically, the Buddha describes blessings that are personal pursuits or attainments, from mundane to spiritual. He specifies that there are 38 highest blessings in life. A person at a particular stage in life has a ‘highest blessing’ appropriate for his or her own individual stage of development. As a person’s situation evolves, what would be the ‘highest blessing’ changes. Working towards further ‘highest blessings’ increases progress along the path towards enlightenment. The 38 blessings are written in stanzas as follows:

“Not to be associated with the foolish ones,

to live in the company of wise people,

honoring those who are worth honoring.

“To live in a good environment,

to have planted good seeds,

and to realize that one is on the right path.

“To have a chance to learn and grow,

to be skillful in one’s profession or craft,

practicing the precepts and loving speech.

“To be able to serve and support one’s parents,

to cherish one’s own family,

to have a vocation that brings one joy.

“To live honestly, generous in giving,

to offer support to relatives and friends,

living a life of blameless conduct.

“To avoid unwholesome actions,

not caught by alcoholism or drugs,

and to be diligent in doing good things.

“To be humble and polite in manner,

to be grateful and content with a simple life,

not missing the occasion to learn the Dhamma.

“To persevere and be open to change,

to have regular contact with monks and nuns,

and to fully participate in Dhamma discussions.

“To live diligently and attentively,

to perceive the Noble Truths,

and to realize Nibbana.

“To live in the world

with one’s heart undisturbed by the world,

with all sorrows ended, dwelling in peace.

“For one who accomplishes this,

unvanquished wherever one goes,

always one is safe and happy.”

Read more : Mangala Sutta: Blessings, translated from the Pali: by Narada Thera

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Og_q4qwjLs

The Dhammapada – full AudioBook | Buddhism – Teachings of The Buddha

Buddhism’s Two Main Lineages: Theravada and Mahayana

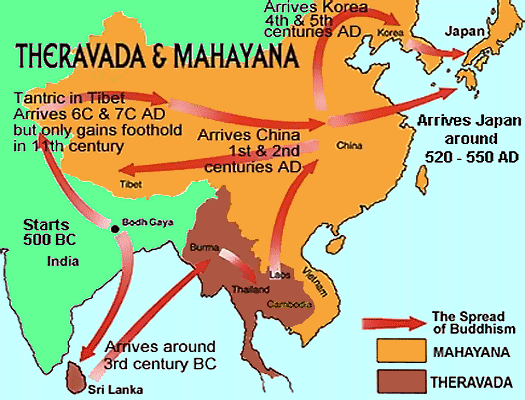

For more than 2,000 years, there have been two main lineages in the Buddhist world: Theravada and Mahayana. Theravada literally means “teaching of the Elders,” and Mahayana “the Great Vehicle”. Theravada was the original Buddhist lineage, while the Mahayana began sometime around 200 B.C.E., likely in northern India and Kashmir.[11] There is no hostility between the two groups.[10] Each sect mainly flourishes peacefully in different parts of the world. Theravada Buddhism now flourishes in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, while Mahayana Buddhism does so in China, Northern India, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Vietnam. Nevertheless, in some countries, both Theravada and Mahayana co-exist peacefully, as in Malaysia and Singapore.

Read more : The Birth and Spread of Buddhism

Read more : The Spread of Buddhism

Theravada Buddhists strive to be arahants, or arhats. Arahants are perfected people who have gained true insight into the nature of reality. This means they have followed the Noble Eightfold Path to extinguish the three fires of greed (Pali: lobha), hatred (Pali: dosa), and ignorance (Pali: moha). They are enlightened. Consequently, they will no longer be reborn in the cycle of samsara.

Read more : Theravada Buddhism in a Nutshell

Read more : Theravada Buddhism Information – History and philosophy

Read more : History of Theravada Buddhism in South-East Asia with special reference to India and Ceylon

Read more : Without and Within, Questions and Answers on the teachings of Theravada Buddhism

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3rBdWCl)

Mahayana Buddhists also believe they can achieve enlightenment through following the teachings of the Buddha. The goal of a Mahayana Buddhist may be to become a Bodhisattva—a status achieved through the Six Perfections (Pali: paramitas) which are virtues to be cultivated. Compassion is very important in Mahayana Buddhism, making many Bodhisattvas choose to stay in the cycle of samsara in order to help others on their own path to enlightenment.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/2O8lgH6)

One Mahayana group which developed by the sixth century in India is known as Vajrayana (meaning Thunderbolt Vehicle or Diamond Vehicle) or Mantrayana (meaning Mantra Vehicle). Its doctrines are close to those of the traditional Mahayana, and it uses many of the Mahayana’s texts, though many of its practices have been developed differently. For instance, one of its practices includes meditative repetitions of sacred words of powers (mantra), as well as visualization practices. It is characterized by the use of texts known as Tantras, a complex system of rituals, symbolism, and meditation.

Read more : Mahayana Buddhism

Read more : Mahayana (Great Vehicle)

Read more : Vajrayana

(Source: https://bit.ly/3t7Uuxd)

Despite the apparent differences between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, the two lineages actually have a lot in common. Dr. W. Rahula for one writes, “I have studied Mahayana for many years, and the more I study it, the more I find there is hardly any difference between Theravada and Mahayana with regard to the fundamental teachings. Both accept the Buddha as the Teacher. The Four Noble Truths are exactly the same in both schools. The Eightfold Path is exactly the same in both schools. The Dependent Origination (Pali: Paticca-samuppada) is the same in both schools. Both rejected the idea of a supreme being who created and governed this world. Both accept anicca (impermanence, transiency), dukkha (the state of being subject to suffering), anatta (not-self), sila (morality), samadhi (concentration, meditation), panya (wisdom), without any difference. These are the most important teachings of the Buddha, and they are all accepted by both schools without question.”

Read more : The Buddhist Schools: Theravada & Mahayana

Read more : Define the terms Theravada and Mahayana and appraise how they relate to each other

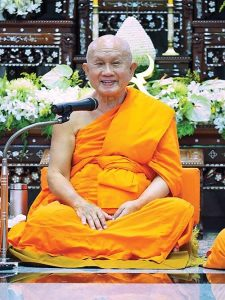

1. A Thai Theravada renowned scholar monk (Pali: Bhikkhu). He is the author of the book

Buddhadhamma: The Laws of Nature and Their Benefits to Life, and many other books. His works were important references for this article.

Read more : Buddhist Monastic Community: The Daily Life of a Thai Monk

Read more : A Monk’s Life: a Day in the Life of Buddhist Monks in Myanmar

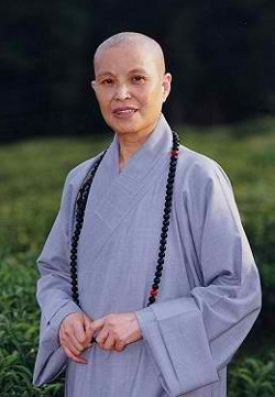

2. Master Cheng Yen, a renowned nun of Taiwanese Mahayana (Pali: Bhikkhuni)

3. Male lay devotees (Pali: Upasaka) (Richard Gere performing a Buddhist Puja at Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Bihar, India, 2020. (Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3t9jPa9)

4. Female lay devotees (Pali: Upasika) A Buddhist Thai princess lay devotee performing a Buddhist ceremony

References

- Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Edward A. Irons, Checkmark Books, 2008, p. XV

- Ibid, p. 4

- Science-Based Benefits of Meditation, p. 67

- The Penguin Dictionary of Religion in India, p. 411

- The Penguin Dictionary of Religion in India, p. 49

- Old Path White Clouds, p. 81

- Old Path White Clouds, p. 82

- https://www.kamaayurveda.com/blog/peepal-tree/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tripi%E1%B9%ADaka

- A Concise Encyclopedia of Buddhism, p. 134

- https://bit.ly/3bD7sgK

Further Readings

- Buddhadasa, Bhikkhu. Anapanasati (Mindfulness of Breathing). at https://bit.ly/2OCmLwZ

- Buddhaghosa. Visuddhimagga translated from Pali into English by Bhikkhu Nanamoli as The

Path of Purification at https://bit.ly/2SiJY9r - HH Dalai Lama. Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment. at https://bit.ly/3lcoQMj

- Jayasaro, Ajahn. Without and Within, Questions and Answers on the Teachings of Theravada

Buddhism at https://mindfulnessexercises.com/without-and-within/ - King, Winston L. Theravada Meditation. at https://bit.ly/3cp2CT8

- P. A. Payutto, Bhikkhu (Phra Brahmagunabhorn). Thai Buddhism in the Buddhist World, A

Survey of the Buddhist Situation Against a Historical Background at https://bit.ly/3uhlTx6 - P. A. Payutto, Bhikkhu (Phra Brahmagunabhorn). The Nectar of Truth: A Selection of Buddhist

Aphorisms, translated from Thai into English by Professor Dr. Somseen Chanawangsa at

https://bit.ly/3vfm7pu - P.A. Payutto, Bhikkhu (Somdet Phra Buddhaghosachariya). Buddhadhamma, The Law of

Natures and Their Benefits to Life, translated from Thai into English by Robin Philip Moore at

https://bit.ly/3famOef - Thich Nhat Hanh. Old Path White Clouds, Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha at

https://bit.ly/3yYbSs3 - Thich Nhat Hanh. The Path of Emancipation. at https://bit.ly/2PSbVng

- Upatissa, Arahant (author). Vimuttimagga, translated from Chinese into English as The Path of

Freedom by Rev. N.R.M. Ehara, Soma Thera & Kheminda Thera at https://bit.ly/2QGYmHX - Weragoda Sarada Maha Thera. Treasury of Truth Illustrated Dhammapada at

https://bit.ly/2SbHxFv

AUTHOR

Paitoon Songkaeo, PhD