If you have ever visited Thailand or are planning a trip to the country, chances are you have come across the term wat, whether it be Wat Phra Kaew (the Emerald Buddha temple) in Bangkok, or Wat Chai Watthanaram in Ayutthaya. Essentially, the term Wat means ‘temple’ in Thai, and in addition to being globally renowned sites, wats are also a quintessential representation of Thai Buddhist architecture: a product of the culmination of Thai spirituality, aesthetics, and cultural identity. In this article we will explore the complexity of Thai Buddhist architecture through these ubiquitous, albeit iconic, religious sites in Thailand.

Photo Credit : novotelbkk.com

Roots and Influences

According to archaeological evidence, it is believed that Buddhism may have spread into the region as far back as the mid-3rd century BCE during the reign of Ashoka the Great, who commissioned waves of Buddhist missionaries into various regions in Asia, including Southeast Asia, then known as Suvanabhumi. However, it was not until around the 6th century CE that the first evidence of Buddhist art in the region that is now Thailand emerged with the rise of the Mon civilization of Dvaravati and its adoption of Theravada Buddhism. Buddhist art in this period sported a significant influence from Southern Indian schools, such as Amravati and Gupta, blended with the local animistic art styles.

Cradle of Mon Civilization of Dvaravati,

Photo Credit : prachachat.net

Nonetheless, Dvaravati influence in the region waned in the late 11th century CE with the rise of the Khmer Empire. In contrast to the Mon, the Khmer worshipped a blend of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, which arrived in the empire through Srivijaya, another significant contemporaneous empire to the south of the Indochina peninsula. During this period, Buddhist art and architecture in the region were particularly influenced by the schools that inspired Bayon and Angkor Wat. One key architecture of the era is the prasat (ปราสาท), or stone temple, which was often built as a place of religious worship and oblation. Concurrently, another Theravada Buddhism worshiping rival kingdom to the Northwest, in the area that is now Myanmar, known as Pagan, emerged, bringing the Burmese art style into the mix.

Photo Credit : travel.mthai.com

Photo Credit : britannica.com

As the first Thai kingdom, Sukhothai, was founded in the 13th century CE, these existing architectural traditions were largely adopted by the kingdom and blended with local art styles, forming the basis for the development of Thai Buddhist architecture later. Incidentally, in the early days of the kingdom, both sects of Buddhism were practiced; however, during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng (1279-1299), Theravada Buddhist monks from Sri Lanka were invited to officially establish a cloister in Sukhothai, cementing Sri Lankan-style Theravada Buddhism as the predominant religion in the area. Additionally, this marked the advent of Sri Lankan architectural styles in the region.

Photo Credit : e-library.siam.edu

Sukhothai Historical Park, Sukhothai Province

Photo Credit : ummio.blogspot.com

In addition to this, the Buddhist architecture in the region was initially predominantly monochromatic; however, with the arrival of Chinese influences, the usage of colors was gradually adopted until it became mainstream. Through these influences, Thai Buddhist architecture became a new distinct, graceful and colorful art style imbued with symbolism.

Materials and Techniques

Traditionally, Thai Buddhist architecture uses materials that are easy to find and work with locally, even though they require regular maintenance over time. These materials include:

Wood

Wood is the most widely used material in traditional architecture. Not only may wood be employed in the construction of the entire building, it can also be exclusively used as the roofing in brick buildings. Alternatively, it may be used as an ornamental piece through elaborate carvings or in conjunction with gilding or glass mosaics. Additionally, owing to its high tensile strength and light weight, wood also often constitutes the structural frame of constructions in traditional architecture. Its versatility, combined with its abundance in Thai rainforests, makes wood the quintessential Swiss-army knife of building materials in traditional architecture.

Chon Buri Province

Photo Credit : ummio.blogspot.com

Brick and Stucco

Clay brick has been in use in Thai Buddhist architecture since the Sukhothai period, whose brick-making method was adopted from the Mon and the Khmer. In its early days, traditional bricks were huge in size in comparison to their modern-day counterpart, measuring up to 13 cm in width and 30 cm in length, and were made with clay from river beds mixed with rice hulls and baked in a traditional brick oven. Furthermore, in this period, bricks were also often used in conjunction with laterite stone (ศิลาแลง), giving various religious heritage sites in Thailand their reddish hue.

Phet Province

Photo Credit : finearts.go.th

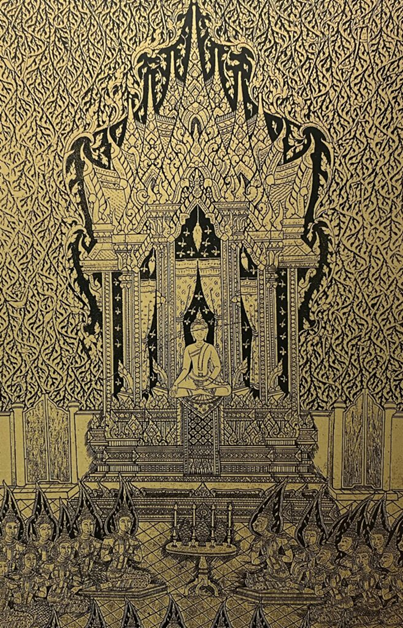

Throughout history, brick-making techniques continued to evolve, giving rise to bricks in many various shapes, such as rhombus-shaped bricks (อิฐหน้าวัว) and wedge bricks (อิฐแบบลิ่ม), which can be used to build a door arch. In most cases in traditional Buddhist architecture, bricks are, owing to their high durability and fire resistance, often used to build the walls of the building, which are frequently coated with stucco. This coating can, then, be molded into various ornamental pieces on the wall, along the door frame, or along the windowsill. The stucco-coated brick walls allowed for its interior to be embellished with tempera murals iconic to virtually every temple in Thailand. These murals often depict scenes from the life of Gautama Buddha, scenes from his past lives (Jataka), or Buddhist cosmology. As an interesting side note, the color red in murals and interior decorations in Thai temples is meant to be interpreted as a void, meaning that nothing is visible in that location.

Embellished with Tempera Murals, Ratchaburi Province

Photo Credit : finearts.go.th

In addition to these key building materials, other, more delicate materials may also be used as ornamental pieces. These include:

Gold Leaf

The thin sheet of gold is often used in Thai Buddhist architecture as a gilding material for ornamental pieces made from wood carvings, stucco moldings, and lacquer designs.

Photo Credit : Reproductions of Jataka stories and the Buddha’s biography from gilded lacquer cabinets. Commemorative edition for the 60th Anniversary of His Majesty the King’s Accession, 2006.

Colored Glass mosaics

Colored glass mosaics are usually used to provide colorful embellishment to gables, pillars, and other wooden or stucco ornaments.

Photo Credit : mgronline.com

Porcelain

In various temples, especially across Bangkok, collections of pieces of broken porcelain wares are frequently used to embellish the surface of some brick structures. For instance, the iconic phra phrang of Wat Arun is beautifully ornamented with invaluable porcelain plates and bowls, mostly imported from China, in various intricate patterns, such as flowers and leaves.

Photo Credit : mgronline.com

Lacquer

Lacquer is frequently used in the decoration of window and door panels. Commonly, the motif on the panel is often gilded, contrasting with the black background.

Photo Credit : sacit.or.th

Inlaid Mother of Pearl

This encompasses the insertion of the elaborately cut inner shell of mollusks into wooden pieces. In Thai Buddhist architecture, this is often used as a decoration for window and door panels.

Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : finearts.go.th

Apart from these, colors are also ingeniously employed to not only communicate symbolically, as with the case with the usage of red to signify the void, but also to both vividly depict mythical figures in interior decorations, and harmoniously blend each structure with the surrounding tropical landscape.

Layout and Key Architectural Elements of a Wat

The centerpiece of Thai Buddhist architecture is naturally the wat, which is essentially the Thai term denoting a Buddhist temple complex. Although the etymology of the term remains ambiguous, many have theorized the term to either stem from the Pali term meaning ‘a place of the discussion of teachings,’ or another denoting ‘duty,’ or, alternatively, from the other referring to ‘the act of determining the boundary of the monastery’.

Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : sanook.com

Photo Credit : rattanakosinislandguide.wordpress.com

In any case, wat can generally be divided into three zones: buddhavasa (พุทธาวาส), sanghavasa (สังฆาวาส) and dharanisangha (ธรณีสงฆ์). The first among the three, buddhavasa, constitutes the most vital area in the temple complex and encompasses the area containing venues designated for the monks to perform religious rituals, and is often enclosed by a gallery, housing Buddha images, known as phra rabeang (พระระเบียง).Main structures in this zone include the following:

Muang Boran Museum, Samut Prakan Province

Photo Credit : finearts.go.th

Photo Credit : Facebook Page

“เกร็ดประวัติศาสตร์ v 2”

Phra Chedi (พระเจดีย์) – Stupa

Considered to be the most venerated religious structure in Buddhism, phra chedi primarily serves to enshrine sacred religious relics, especially the earthly remains of Gautama Buddha. Believed to have been derived from ancient Indian burial mounds, phra chedi functions as a memorial to the deeds of an important figure. It, hence, comes as no surprise that stupas in Thailand frequently commemorate the enlightenment of the Buddha as well as the dissemination of his discovered wisdom, reminding worshipers of his grace.

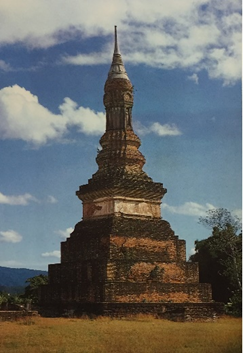

Even though phra chedi often varies in design depending on the regional architectural styles or the historical period, they can generally be grouped into four main designs: (1) spherical (เจดีย์ทรงกลม), (2) octagonal (เจดีย์แปดเหลี่ยม), (3) quadrilateral (เจดีย์สี่เหลี่ยม), and (4) mixed (เจดีย์แบบเบ็ตเตล็ด). Most stupas consist of four main parts: (1) the base; (2) the tumulus; (3) the cubical chair, representing the seat of the Buddha; and (4) the chat (ฉัตร), or the umbrella-shaped pinnacle.

In the temple complex, the primary stupa is either placed in the middle, or behind the uposatha hall or the Vihara, whereas secondary stupas can be complementarily placed around the temple’s main building, whether in rows (เจดีย์ราย), in groups (เจดีย์หมู่), or in each corner (เจดีย์ทิศ).

Si Satchanalai Historical Park, Sukhothai Province

Photo Credit : gplace.com

Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : go.ayutthaya.go.th

Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : bloggang.com

Photo Credit : th.freepik.com

Photo Credit : wongnai.com

Phra Prang (พระปรางค์)

A similar structure to phra chedi, phra prang is a tower-like structure derived from the design of the corner tower of Khmer temples, which are in turn derived from Indian architecture. Consisting of a raised square base and dome-shaped roofing with three niches, a main front entrance, and an interior containing Buddha images, the structure symbolizes Mount Meru, the center of the universe in Indian cosmology. This axis mundi represents Bodhisattva, or the past incarnations of Gautama Buddha, who is believed to be the ‘central ideal of all being’. Phra prang also sports various designs ranging from the solid design (ปรางค์ทรงงาเนียม) to the corncob design (ปรางค์ทรงฝักข้าวโพด) to the unique elaborate design of the phra prang of Wat Arun known as Prang Song Jomhae (ปรางค์ทรงจอมแห). Initially, the structure was often considered a complementary part of the uposatha hall but has since become its own structure. Incidentally, from around the turn of the 17th century CE onward, the design of phra prang was further refined to give its modern, familiar appearance, more distinct from Khmer temples.

Photo Credit : th.wikipedia.org

Uposatha (พระอุโบสถ) or Bot (โบสถ์) – Ordination Hall

A bot refers to the building where sacred rituals pertaining exclusively to monks take place, such as the ordination ceremony. The hall sports a rectangular plan with intricate overlapping roofs as well as embellished gables, and houses a large sitting Buddha figure placed on a high pedestal. Initially, bots were comparably tiny in size and placed insignificantly in the buddhavasa zone. Over time, however, as the population grew, bots became much larger and were placed more towards the core of the zone until around the mid-Ayutthaya period (1448-1668) when it became the main building of a wat in Central Thailand. Notably, the periphery of the structure is decorated with bai sema (ใบเสมา), a stone megalith consecrating the ground over which the structure is erected.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Photo Credit : bloggang.com

Vihara (วิหาร)

In contrast to the uposatha hall, the vihara is used for religious ceremonies involving both the monks and lay devotees. In other words, this would be where the Thais gather to make merit (ทำบุญ). Furthermore, vihara also houses Buddha images and may also contain the temple’s main Buddha image. Architecturally, the structure sports many identical characteristics of the bots, but are not marked by bai sema. Formerly, the Vihara used to be the most significant structure of a temple complex, but has since, at least in Central Thailand, lost its significance to the uposatha hall.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Mondop (มณฑป)

The squared structure with the pyramidal pointy roof is used primarily to house sacred relics, such as the footprint of Gautama Buddha at Wat Phra Phutthabat in Saraburi. Alternatively, it can also serve as a library for scriptures or as a storage space for equipment used in religious ceremonies. In some mondop, the roofs can be intricately decorated with broken porcelain.

Photo Credit : dhammathai.org

Prasat (ปราสาท)

Derived from Khmer temples, prasat is a square sanctuary consisting of a rising dome-shaped tower, or shikhara, on the roof and four porch-like antechambers. The interior of the structure may comprise a square central room with either three projecting long wings and one short, or four wings of equal length. Functionally, prasat may serve as a pavilion for royal or ceremonial purposes, or as a storage place for highly venerated relics, such as the statues of the monarchs of the current dynasty in Prasat Phra Thep Bidon at Wat Phra Kaew.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Ho Rakhang (หอระฆัง) – Bell Tower

Ho Rakhang is primarily used to house the bell which signals the time of rituals for monks. Sometimes, a ‘drum tower’ (ho klong หอกลอง) is also built adjacent to the belfry, and is used to signal mealtime, or used in an emergency. Initially, the belfry was located in the sanghavasa zone but has since the early Rattanakosin period (1782-1804) been moved into the buddhavasa zone.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Sala (ศาลา) – Pavilion

Sala denotes an open pavilion that serves as a resting spot for visitors or as a venue for sermons. Architecturally, the structure is usually laid out rectangularly, and is erected over four pillars, upon which a steep roof with overhanging eaves sits, providing the people inside with protection from the elements as well as extra shade. Additionally, sala is also commonly built outside of a wat to provide resting spots for travelers along the roads. While resting, the structure provides a place for people to socialize, thus serving as an important representation of Thai social life.

Photo Credit : watben5.com

The second zone in the wat, the sanghavasa, encompasses the residence of the monks and is not used to perform any religious rituals. Its key structures include the following:

Kuti (กุฏิ) – Dwellings

Kuti constitutes the structure where the monks reside. The size of the Kuti is generally determined to be around 3×1.75 meters, with rooms enough to house a monk according to monastic rules. The appearance of this simplistic yet functional monks’ residence often corresponds to traditional housing.

Photo Credit : db.sac.or.th

Ho Trai (หอไตร)

Ho trai encompasses the library where scriptures are kept. The design of the library often varies depending on the region. Formerly, the structure was often built over a pond to provide the scriptures with protection from pests. In certain temple complexes that are huge in size, there can be more than one ho trai.

Photo Credit : thetrippacker.com

The final zone of the wat, dharanisangha, refers to any other area within the boundary of the temple complex that is dedicated for public uses, such as the crematorium and the cemetery, or public schools, as well as flea markets. The existence of this naturally signifies the role of wat in traditional Thai society as a center where people can gather and socialize.

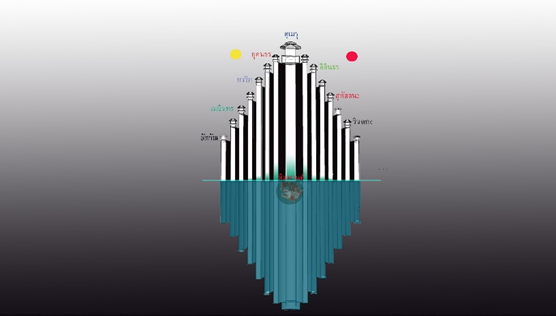

Symbolism and Aesthetic Harmony

In temple designs, symbolism relating to Buddhism and Buddhist cosmology is often embedded into the architecture. For instance, both the stupa and phra prang embody Mount Meru, the center of the universe, while their respective complementary components form the various continents of the world according to the Indian cosmology, both of which, in turn, form a microcosmic replica of the universe. Furthermore, this symbolism of Mount Meru also represents the Buddha and his teachings as the central unifying principle in the universe.

Photo Credit : silpa-mag.com

Aside from this, the multilayered overlapping roof tiers on many uposatha halls and vihara serve to, apart from their practical purpose in warding off the elements, symbolize the various levels of spiritual attainment according to Buddhist metaphysics, with each level reaching closer to Nirvana: transcendence from suffering. At the ends of temple roofs are decorative finials called chofa, along with naga-shaped details on the roof edges known as hang hong. These ornaments are believed to protect the temple from evil.

(Aphorn Phimok Prasat Pavilion) at the Grand Palace, Bangkok

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : silpa-mag.com

Inside temples, murals often tell stories from the Buddha’s life, his past lives, or Buddhist beliefs, and the decorations are based on Buddhist symbols. For instance, the recurring motif of the Dharmachakra (Wheel of Dharma) serves to symbolize the cycle of Dharma. Alternatively, the ubiquitous blooming lotus motif signifies enlightenment, whereas the motif of floating lotuses, often appearing on the ceiling either alongside or surrounded by stars, represents transcendence from suffering.

12th Buddhist Century (7th Century CE). Found at Wat Saneha, Nakhon Pathom Province.

Currently in the collection of the National Museum Bangkok.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Lastly, it is important to note that in Thai Buddhist architecture, great emphasis is always placed on harmony and balance between various elements when it comes to the form, proportion, and ornamentation. This, in conjunction with the implementation of materials of lower durability and the expressed motifs previously discussed, encapsulates the Buddhist ideals of balance, impermanence, and enlightenment that form the foundation of Buddhist belief in Thailand.

Regional and Historical Styles

Sukhothai (mid 13th – early 15th century CE)

Considered by many to be the first independent Thai kingdom in the region, Buddhist architecture of the Sukhothai era is often marked by its simplistic yet elegant nature, as well as its closeness to the source in Sri Lanka and Pagan, while becoming more distinct from the predominant Khmer style. The plan of the temple complex from this era remains highly simplified, with the complex of the main stupa and vihara as the center of the monastery. The floor plans of both the vihara and the uposatha hall exhibit a simple rectangular shape with simple traditional roofing. Ornamental pieces from this period consist mainly of embedded stucco sculpture and ceramic sculpture (เครื่องสังคโลก).

Photo Credit : travel.trueid.net

In any case, exemplary of the architecture from this era are the so-called bell-shaped stupas (เจดีย์ทรงระฆัง), as well as bell-shaped stupas with surrounding elephant carvings (เจดีย์ทรงช้างล้อม), inspired by those found in Sri Lanka, further corroborating the adoption of and the reverence for Sinhalese Theravada Buddhism in this period. Nonetheless, over time, a new style of phra chedi unique to the Kingdom also emerged: the lotus-bud-shaped stupa (เจดีย์ทรงพุ่มข้าวบิณฑ์). In contrast to the bell-shaped upper structure, the stupas in this style sport a columnar upper structure upon which sits a small lotus-shaped component, which extends upward to form a pinnacle. The Buddhist architecture in the Sukhothai era is considered to be the foundation for the traditional architecture in later periods.

Photo Credit : finearts.go.th

Si Satchanalai Historical Park, Sukhothai Province.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Chiang Mai Province.

Photo Credit : tat.or.th

Photo Credit : silpa-mag.com

Ayutthaya (mid 14th – mid 18th century CE)

Being a successor of the Sukhothai Kingdom, the architecture of the Ayutthaya Kingdom exhibits a more grandiose and regal quality with more elaborate designs and ornamentation, while still maintaining the core design from the Sukhothai era. Of note is the more apparent Khmer influence in the architecture with the introduction of phra prang in this era, which started off with a more solid and thicker design closer to the original tower structure, and was over time developed to sport a slenderer as well as more towering design seen in the corncob style. Likewise, the stupa in this era followed the same development. Apart from the bell-shaped design as previously found in the Sukhothai era, a new design sporting an amalgamation of the bell-shaped design with that of phra prang, known as chedi yo mai (เจดีย์ย่อไม้), also emerged in this period. However, in contrast to Sukhothai style, the uposatha hall became the main building of the temple complex and became more intricately built, with the introduction of multi-tiered roofing, a decorated gable with intricate motifs, and window panels. Decorative techniques from foreign cultures, such as China, the Western world, and the Islamic world, also began to be implemented in the ornamentation, such as the use of inlaid mother of pearl in the decoration on door panels.

at Wat Kasattrathirach, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province

Photo Credit : silpa-mag.com

Rattanakosin (late 18th century CE – present; Bangkok)

In the earliest days of the period, the architectural tradition appeared to largely be a continuation of the late Ayutthaya period. In other words, the early Buddhist architecture in this era largely encompassed the restoration of Ayutthaya’s art styles after the kingdom’s collapse in 1767 CE. Later, more elements from foreign artistic traditions were integrated, especially during the reign of King Rama III (1824-1851), when Chinese architectural designs were widely adopted. This new architectural style, commonly known as Sathapattayakam Baeb Phrarachaniyom (สถาปัตยกรรมแบบพระราชนิยม; lit. architectural style according to his majesty’s preference), exhibits a perfect mix of Chinese architecture with Thai; i.e., the religious structures within the temple complex, along with their floor plans, remain fundamentally identical to those traditionally used, but religious symbolism, ornamentation techniques, and roofing style bear a heavy Chinese influence. The architecture in this style also sports more vibrant colors, similar to the architecture found in China. Furthermore, iconic of the ornamentation technique in this style is the use of broken Chinese porcelain as decorative pieces.

at Wat Ratchaorasaram Ratchaworawihan, Bangkok

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Later, at the height of European imperialism in the 19th century CE, the Chinese art style waned in popularity. Instead, western architecture began to play an increasingly significant role in Thai Buddhist architecture, with some wats even bearing an uposatha hall that resembles a combination of western and Thai architecture, such as Wat Mani Cholakhan in Lopburi. This architectural period continues to the present day, incorporating modern schools of architecture into the long-enduring tradition, giving birth to various ingenious structures that bridge the old with the new.

Photo Credit : dhammathai.org

Lanna (Northern)

Once constituting one of the most significant kingdoms in the area that is now Northern Thailand, the traditions of the Lanna Kingdom form the unique foundation of Buddhist architecture in most of the Northern provinces in Thailand, distinct from those in central Thailand. One distinguishing feature of the Lanna architectural style is the variety of unique stupa shapes. Among the oldest forms of stupa, descended from Haripunjaya art, in Lanna is the multi-tiered overlapping stupa (เจดีย์ทรงปราสาทซ้อนชั้น), which can bear either a quadrilateral or circular base, the latter of which gave rise to the unique gourd-shaped stupa in the region. Whereas the Ayutthaya kingdom adapted the Khmer-style temple into phra prang, the Northern Kingdom integrated the design of the temple into their chedis, resulting in the structure bearing a body of the Khmer temple, but with an unaltered pinnacle (เจดีย์ทรงปราสาทยอดเป็นเจดีย์). In addition to this, some stupas in the North may also bear a solid multi-layered overlapping body in various different shapes (เจดีย์ที่มีเรือนธาตุเป็นฐานทึบ).

Photo Credit : li-zenn.com

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Another distinguishing feature of Lanna Buddhist architecture is the higher significance of vihara, often constituting the largest and central structure in the temple complex. Furthermore, the building also frequently sports multi-tiered overlapping roofing. The ornamentation is often done with wood carving, and may be gilded or adorned with colored glass mosaics, although stucco may also be used in certain parts, such as windowsills. Although ho trai in styles similar to those found in central Thailand can also be found, the most common design in the northern part of the country is the double-story ho trai with the lower floor being made from brick and stucco and the second floor made from wood (หอไตรสองชั้นแบบครึ่งไม้ครึ่งตึก).

Chiang Mai Province

Photo Credit : blogger.googleusercontent.com

Isan (Northeastern)

The architecture of the Northeastern part of the country bears striking similarities to that found in Laos. Unsurprisingly, these two regions once belonged to the same cultural sphere, namely, the Lanxang kingdom. Once again, one of the most distinguishing features of Buddhist architecture here can be found in the designs of the stupa. In Isan style, as the area was once largely situated in the Khmer empire’s sphere of influence, many of the designs draw inspiration from Khmer temples, which can be, for instance, seen in Phrathat Phanom and Phrathat Tatthong. Other unique designs in Isan include lotus-shaped and octagonal stupas, as can be seen in Phrathat Khamkaen and Phrathat Hanthao, respectively. Aside from these, the uposatha hall, known in the region as sim (สิม), also differs greatly from its counterpart in central Thailand. Sim can be built on land like the more conventional uposatha hall or raised above a body of water. Furthermore, the structure can also be either fully enclosed (สิมทึบ), surrounded by walls on four sides, or partially enclosed (สิมโปร่ง), with a fully erected wall only behind the Buddha figure. In contrast to the conventional uposatha hall, sim can also sport unique ornamental finials in the middle of the roof, with shapes mirroring those of the stupas found in the region.

Roi-Et Province

Photo Credit : isan.tiewrussia.com

Srivijaya (Southern)

Not many structures remain from the Srivijaya Empire, a powerful state that is today a part of Southern Thailand and predated even the Sukhothai kingdom. In general, stupas influenced by the artistic style from this era exhibit a shape not unlike a mondop (เจดีย์ทรงมณฑป), with a quadrilateral base and body, and an octagonal pinnacle. Today, the only surviving stupa from this period can be found at Wat Phra Borommathat Chaiya in Surat Thani Province. Later, after the decline of the kingdom, a new influence from Sri Lanka replaced the Srivijaya style, resulting in many stupas in Southern Thailand bearing a resemblance to those found in Sri Lanka, paralleling as well as kick-starting the development in Sukhothai.

Photo Credit : cbtthailand.dasta.or.th

The Legacy of Thai Buddhist Architecture

Despite having roots in the ancient world, Thai Buddhist architecture is still relevant and going strong in today’s society. For one, temple architecture in the country is still constantly evolving, with architects incorporating modern architectural techniques and styles while still maintaining traditional principles at the core. Notable examples of these include Wat Rong Khun (also known as the White Temple) and Wat Pariwat Rachasongkhram. The former was once a small temple in Chiang Rai, but was renovated by Chalermchai Kositpipat, a renowned national artist hailing from the province, and now features one of the most stunning and highly intricate wood carving architectures drawing inspiration from Buddhist symbolism. The latter, on the other hand, situated in Bangkok, features a vibrant uposatha hall with modern plaster sculptures as ornamental pieces, whose motif, unexpectedly, not only depicts Buddhist symbolism, but also pop culture references, such as cowboys and even David Beckham.

Apart from the contemporary designs of wats, many existing temple complexes are also actively being restored in accordance with their traditional designs by the Fine Arts Department to help preserve the age-old traditions. Lastly, although Thai temples have always served spiritual purposes for the Thais, the religious sites have since become much more recognized in the cultural tourism landscape, serving as a window from the modern world into the quaint traditional world.

Photo Credit : upload.wikimedia.org

Values Reflected in Thai Buddhist Architecture

As a priceless tradition, Thai Buddhist architecture encapsulates many core values that underpin Thai society. First and foremost, the architectural tradition reflects the significance of Buddhism in Thai society, which translates into the Thais’ high reverence for the religion. In this regard, not only can the practice of building temples be regarded as one of the highest forms of merit making, it also helps to greatly bolster the religion, and is a gesture of worshiping the threefold refuge – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha – that forms the three foundational pillars in Buddhism. Temples also embody the Thais’ great respect for their own community through breathtaking architecture, while functioning as a public space where people can gather and nurture social relationships.

Photo Credit : jinnyz.com

Secondly, the tradition represents the value of harmony. For one, temples are always designed to coexist harmoniously with their surroundings, gracefully blending the grandiose elegance of the structure with the simplistic tranquility of nature, mirroring the Buddhist teaching of the middle path. Aside from this, the tradition also promotes harmony between the religion and the community, offering a place where laymen can come seek spiritual attainment while the clergy can further proselytize and deepen their understanding of their own religion.

Chachoengsao Province.

Photo Credit : tbmccs.go.th

Thirdly, through the intricate carvings, vivid mosaics, and mystical motifs, the Thais’ ingenuity and creativity are showcased. In this regard, the Thais take tremendous joy in conceiving great art pieces, whose beauty is offered as an act of piety rather than to satisfy personal glory. This great enjoyment also results in the Thais always perfecting and improving their craft. Fourthly, the practice also illustrates the Thais’ openness in being highly receptive to adapting other cultures to augment their own. This can be seen in the blending of Indian, Khmer, Chinese, and other art styles with local influences in Thai Buddhist architecture. The Thai spirit of acceptance and adaptability is truly highlighted in this regard.

Lastly, drawing on the Buddhist teaching of balance and spiritual attunement, the tradition also serves as a sanctuary from the modern hectic world, where all are invited to channel their mindfulness and attain inner peace, truly embodying a lesson in the lost art of calm living in the modern world.

Photo Credit : chillpainai.com

Conclusion

As can be seen, Thai Buddhist architecture is more than just artistic expression; it is a living dialogue between faith, history, and creativity – truly a living monumentum fidei. In this way, every wat or temple complex in Thailand recounts a story of devotion, craftsmanship, and cultural as well as religious identity: a timeless embodiment of Thainess.

Thai Buddhist architecture is a crucial and enduring aspect of Thai culture and heritage. Thailand’s temples reflect the country’s faith, artistry, and sense of community. Join us as we explore more stories of Thailand and its people, and discover the essence of Thainess together.

Sources

พระราชเมธีวชิรดิลก (ไพจิตร สาฆ้อง), พระครูสุนทรธรรมนิเทศ (จารุวัฒน์ จันทะพรม), พระมหาทศพรสุมุทุโก (อ่อนน้อม), ชาญพัฒน์ ขำขัน และวรวุฒิ สุขสมบูรณ์. (2024). พุทธศิลป์ในประวัติศาสตร์: การสร้างสรรค์และการแสดงออกทางศาสนา. วารสารมณีเชษฐารามวัดจอมมณี, 7(6), 1420-1438.

ธนู ศรีทอง, บรรจง โสดาดี และบูรกรณ์ บริบูรณ์. (2016). ภูมิศาสตร์วัฒนธรรม: ประวัติศาสตร์ เส้นทางการเผยแผ่พระพุทธศาสนา และหลักพุทธธรรมในสมัยอยุธยา. กรุงเทพฯ: มหาจุฬาลงกรณราชวิทยาลัย.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Dvaravati

https://www.wagnermeters.com/moisture-meters/wood-info/advantages-wood-building

ภราดร ชุไชยสงค์ และสุพรรณ วงทอง. (2009). การศึกษาคุณสมบัติของอิฐมอญที่ผลิตในจังหวัดชลบุรี. ชลบุรี: มหาวิยาลัยบูรพา.

https://www.silpa-mag.com/history/article_20752

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/craftsmanship-of-mother-of-pearl-inlay-01874

https://www.britannica.com/topic/stupa

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4554109731306440&id=143050959079028&set=a.144196492297808

สุรพล ดำริห์กุล. (2019). สถาปัตยกรรมที่เป็นเอกลักษณ์ของสุโขทัย. วารสารข่วงผญามหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏเชียงใหม่, 14, 44-85.

ธาดา สุทธิธรรม และคณะ. (2002). สถาปัตยกรรมวัดพุทธศาสนาในประเทศไทย: วัดภาคเหนือและภาคกลาง. กรุงเทพฯ: ศูนย์มานุษยวิทยาสิรินธร. ฐานข้อมูลงานวิจัย ศมส.: http://sac-research.sac.or.th/research_pdf_pdf.php?file_id=1033&ob_id=33

ธาดา สุทธิธรรม และคณะ. (2002). สถาปัตยกรรมวัดพุทธศาสนาในประเทศไทย: วัดภาคใต้ ภาคอีสาน และภาคตะวันออก. กรุงเทพฯ: ศูนย์มานุษยวิทยาสิรินธร. ฐานข้อมูลงานวิจัย ศมส.: http://sac-research.sac.or.th/research-item-search.php?ob_id=34

ชาตรี ประกิตนนทการ. (2013). ศิลปะ-สถาปัตยกรรมสมัยรัชกาลที่ 1: แนวคิด คติสัญลักษณ์ และ ความหมายทาง สังคมยุคต้นรัตนโกสินทร์. Journal of Fine Arts, Chiang Mai University, 4(1), 243-324.

ณัฐวัตร จินรัตน์. (2003). การออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรมแบบพระราชนิยมในรัชกาลที่ 3 (ศึกษาเฉพาะเขตพุทธาวาสของพระอารามหลวงที่สร้างขึ้นในสมัยต้นกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์). กรุงเทพฯ: มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร.

สันติ เล็กสุขุม. (2000). จิตรกรรม ประติมากรรมในวัดพุทธศาสนาในประเทศไทย. กรุงเทพฯ: ศูนย์มานุษยวิทยาสิรินธร. ฐานข้อมูลงานวิจัย ศมส.: http://sac-research.sac.or.th/research-item-search.php?ob_id=13

https://kk.mcu.ac.th/Art-Culture/files/013sim.pdf