Photo credit: DTH Travel

For many who have visited Thailand, one of the most familiar sights in the souvenir shops is Thai silk, with its iconic motifs and colorful variations. Yet, Thai silk is just the tip of the iceberg in the country’s rich and diverse fabric and textile traditions. Deeply rooted in history and incorporating many regional identities, the traditional craft plays a significant role within Thai society, both in daily life and even more so in ceremonies. In this article, we will “weave” through the tapestry of Thai textile traditions in all of their multi-faceted, essential aspects, from the materials used and natural dyeing practices, to weaving and decorative techniques, as well as their cultural significance.

History

Evidence of the earliest local textile traditions in Thailand dates back to prehistoric times. Discovered in Ban Chiang archaeological site in Northeastern Thailand, fabric scraps as well as weaving tools and clay rollers, theorized by archaeologists to be used as fabric printing molds, signify how deeply ingrained the craft has been in Thai culture. Throughout different periods in Thai history, traditional textiles continued to be interwoven within the culture, as evident from the mentioning of various types of traditional fabrics in many historical accounts, as well as literature. One such interesting account is the Legend of Old Palace from the 63rd volume of the Historical Annals of Ayutthaya, which speaks of Wat Khun Phrom, a district well-known for its printed fabric. However, after the Second World War, fabric and textile production in the country was largely industrialized, leading to the replacement of traditional fabric by its mass-produced, Westernized counterpart for several years. Nonetheless, in 1965, traditional weaving was once again revitalized by an initiative of Her Majesty Queen Sirikit who sought to promote traditional crafts. In this light, Her Majesty has been using traditional fabric to have her outfits designed, donning them with pride when conducting royal duties both domestically and internationally, setting trends for the revived appreciation of classical textiles. Moreover, the Queen also established the SUPPORT Foundation for Arts and Crafts (มูลนิธิศิลปาชีพ) to further bolster the production, as well as the vocational education, of various local arts and crafts, including, of course, traditional textiles. Later, in the early 2000s, a local entrepreneurship stimulus campaign by the government known as OTOP (One Tambon, One Product) further breathed new life into the traditional fabric landscape, which saw its resurgence as valuable commodities through which various local communities throughout the country could preserve and commercialize their local fabrics.

Photo credit: Tourism Authority of Thailand

Photo credit: Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles

Photo Credit: The Support Foundation for Arts and Crafts

Photo Credit: OTOP Thai Shop

The Materials

Although, nowadays, synthetic fibers such as rayon may also be used in traditional textile production, natural fiber remains the first and most popular choice for the material. It is often woven using a traditional weaving loom, known in Thai as กี่ (kii) or หูก (huuk) into a whole piece of cloth. Different intricate decorative patterns can be added in the process by using additional tools, which will be covered later in the article. Among the most common natural fibers used are:

Photo Credit: Dobby Tex

- Silk

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

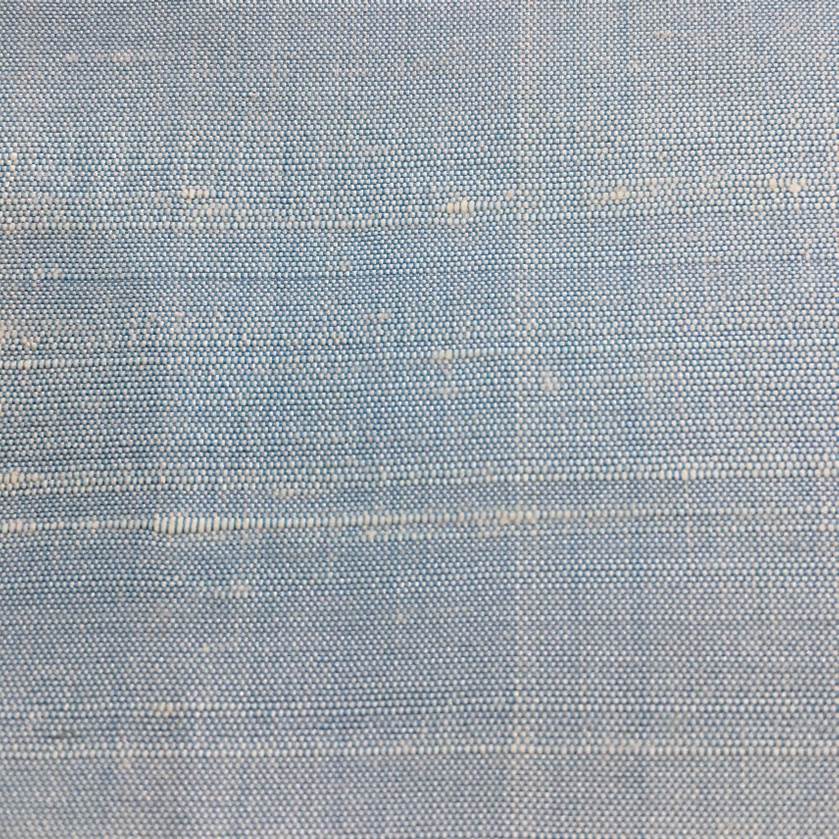

As the most exquisite material in classical fabric production, Thai silk signifies the elegance and beauty embedded within the culture. The silk is obtained through an arduous process, requiring thoroughness to ensure top quality. The process begins with the rearing of silkworms with mulberry leaves. Once the worms metamorphose into silk moths, the cocoons are collected and reeled into silk threads, a process known in Thai as สาวไหม (Saao Mai). Although silk is also produced in other parts of the world, the main distinguishing feature of Thai silk lies in its unique glistening, fluffy and soft texture, while still being dense.

As highly valued as it might be, silk weaving was ultimately not spared from a drop in popularity post-Second World War due to the rapid industrialization of fabric production, as was the case with traditional fabric production in general. With the revitalization and popularization of Thai silk through the aforementioned crafts-promoting campaign, H.M. Queen Sirikit also funded research and development of traditional silk production, while always donning outfits made from silk to further symbolize Her Majesty’s patronage of the craft. Furthermore, in 2007, the Royal Peacock badge or ตรานกยูงพระราชทาน (Traa nokyuung praraatchathaan), a quality seal to assess the quality of produced Thai silk, was launched by Her Majesty, categorizing the textile into royal, classic, normal and blended grades.

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

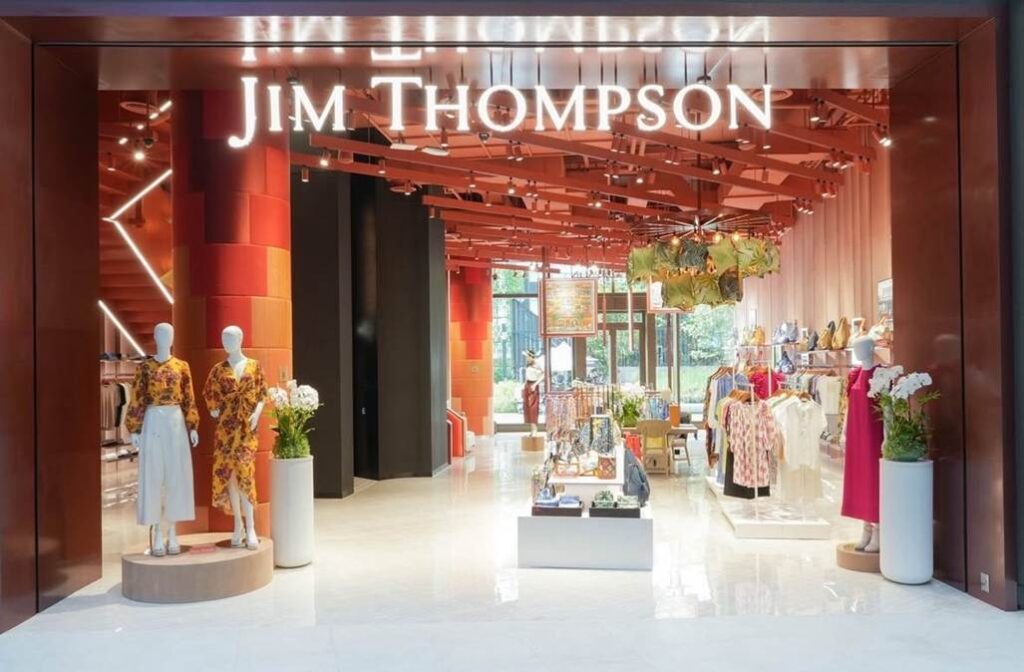

Another important revitalization effort came in the 1950s in the form of The Thai Silk Company Ltd., established by an American architect, James H.W. Thompson, with the aim to restore and preserve the then declining craft of Thai silk weaving. Striving for “design excellence and community empowerment”, the company catapulted traditional silk production into the international fashion industry scene. Today, the company, now known as Jim Thompson Corporate, honoring its founder, still sells exquisite fashionable clothing articles, as well as home furnishings made from artisanally woven traditional silk, with its products also appearing in the currently popular third season of HBO’s The White Lotus.

Photo credit: Travel Daily Media

Today, in addition to its title as a famed, luxurious material within the fashion industry, Thai silk plays an important role in the economy as an export commodity, supporting silk-raising and weaving communities throughout the kingdom.

- Cotton

Photo credit: Thairath

Dominating as one of the most used materials in the textile industry, it comes as no surprise that cotton is indeed also used in Thai traditional fabric weaving. Cotton fiber is obtained from cotton plants, which is then spun and woven into pieces of cloth. Cotton is beloved for its durability, high absorbent quality, high elasticity and high heat resistance, combined with its high breathability and comfort. This makes it a very suitable choice for use in everyday wear, such as, traditionally speaking, in mor hom shirts and in sarongs, as well as home textiles, such as curtains, towels and bedding. In Thailand, cotton is usually grown in plantations in the Northern and Northeastern regions of the country, and subsequently supplied to local handicraft community enterprises and small local businesses.

Photo credit: OTOP Chiangmai

- Hemp

Photo credit: Sarakadee Lite

Widely used among the hill tribes, such as the Hmong and the Akha peoples, hemp is highly durable while also being sustainable, requiring less land to be cultivated, and improving the surrounding environment. Traditionally, among the hill tribes, hemp fiber is first evenly peeled from the plant’s stem, after which the fiber is hang-dried and crushed to increase its softness. After being hung in the open until completely dried, the fiber is connected together by hand, then disentangled and processed before being boiled. The prepared fiber is then woven into cloth, dyed, and subsequently decorated with the unique patterns of each hill tribe before being made into different articles of clothing. Apart from representing the unique identities of the hill tribes, hemp fabric has increasingly gained traction in modern eco-conscious design.

Photo Credit: Thairath

The Dyes

Once the natural fiber is woven into a complete piece of cloth, the fabric is often dyed, not only to enhance its beauty but to increase its value, both monetarily and culturally. Within classical practices, natural dyes are used, which are often sourced from locally available materials within each region of the country, resulting in a myriad diverse dyeing traditions. Some interesting examples include:

- Indigo Dye

Photo credit: Matichon Online

Traditionally, indigo dye was sourced from two tropical plant species, the indigo plant คราม (khraam) and Baphicacanthus cusia, or ฮ่อม (hom). The former is mostly grown in the Northeastern part of Thailand where it is, unsurprisingly, widely used. In particular, Sakon Nakhon province has garnered a reputation as one of the best producers of indigo-dyed fabrics. To acquire the dye, the indigo leaves are usually submerged in a basic solution and left to sit for several days to allow the dye to deposit as sediment. Dyeing with indigo employs a “cold dyeing” process. First, the obtained sediment is dissolved in an alkaline solution, after which the cloth is submerged in a vat, and subsequently taken out to squeeze out excess liquid. The process is then repeated at least thrice, until the desired shade is achieved. As cold dyeing does not require additional heating of the solution, the process is thought to be environmentally friendly and energy efficient. Characteristically, due to being water insoluble, the dye is not susceptible to bleeding.

Photo Credit: The Cloud

On the other hand, the Baphicacanthus cusia, or hom plant,is mostly grown in the Northern region of the country. Known in Thai as ม่อฮ่อม (mor hom), the word for the dyeing technique involving the material is derived from the Northern Thailanguage meaning “dark indigo hue”. To extract the dye for use, the plant is crushed and soaked in starch water obtained from washing uncooked rice for several days, after which the deep blue-hued water is decanted, to which a basic solution is added to allow the dye sediment to precipitate. Similar to indigo plant dyeing, the dye sediment is dissolved in an alkaline solution, but unlike the former, the mixture is allowed to sit overnight before use. When dyeing, the cloth is submerged in a vat around 2-3 times until the desired shade is achieved. Similarly, mor hom also employs cold dyeing, as with indigo plant dyeing. Today, one of the most popular places to buy mor hom is Phrae province, with myriad vendors selling clothing articles with various unique designs made with the fabric, as well as workshops for those interested in learning the craft.

Photo credit: Banfai Chiangrai

- Lac Dye

One of the most ubiquitous hues in Thai traditional fabric production, both in the court and among ordinary folks, is the vibrant pink to red tone derived from lac, a species of tropical scale insect. Feeding on the sap of certain plants, such as sacred figs, the insects secrete shellac, a type of resin, which is reddish in color, as their protective covering. This is harvested to be used as a dye. In certain parts of the country, lacs are also cultivated for this reason. In processing the shellac for dyeing, it is firstly cleaned of any scraps and dirt, and then finely ground. Subsequently, the resin is soaked in clean water overnight or stirred in boiling water before being strained for the pigmented liquid, which is then boiled once more. The remaining residue is then filtered out, and the dye is ready for use. In the traditional dyeing process, both cold and hot dyeing are used. Additionally, tamarind juice and alum are added to control the shade and act as a mordant, respectively.

Photo credit: Northern Shellac

The Styles

One of the most intriguing features of Thai fabric and textile heritage are its rich and diverse decorative and patterning techniques, a lot of which have their roots within, or are adapted from, age-old traditions to suit the contemporary context. Among the most outstanding examples of these are:

- Tabby Weave

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Also known as plain weave, the tabby weave constitutes one of the most basic and ubiquitously-used weaves. The weave is formed by fixing threads onto the weaving loom vertically (warp), and winding another set of threads horizontally (weft) through, crossing each weft over and under each warp into a somewhat checkered pattern. Due to its simplicity, the weave serves as a foundational technique in many regions across the country, functioning as a substrate for more intricate patterns.

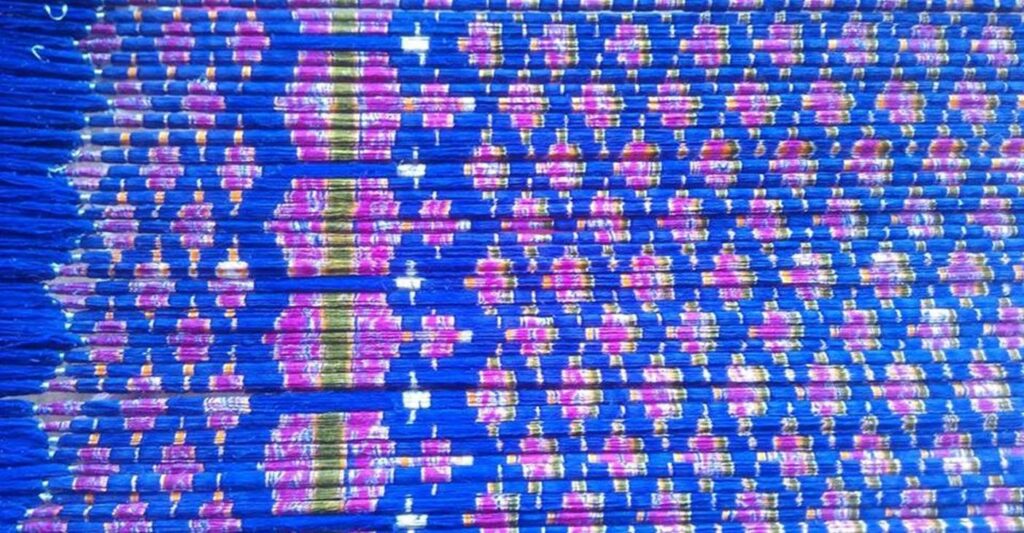

- Mat Mii

Widely used in the Northeastern part of Thailand, mat mii (มัดหมี่), also known as ikat, is a process in which the threads are tied off in a predetermined sequence with dye-resistant materials, such as strips of banana leaves, to create a desired pattern before dyeing, resulting in the pigment not being absorbed by the fabric in the tied-off sections. This process can be repeated until the desired colors and patterns are achieved, after which the threads are either used as the weft (มัดหมี่เส้นพุ่ง /mat mii sen pung/) or the warp (มัดหมี่เส้นยืน /mat mii sen yuen/) depending on preference, although the former is more commonly preferred.

Photo credit: Sirindhorn Isan Information Center

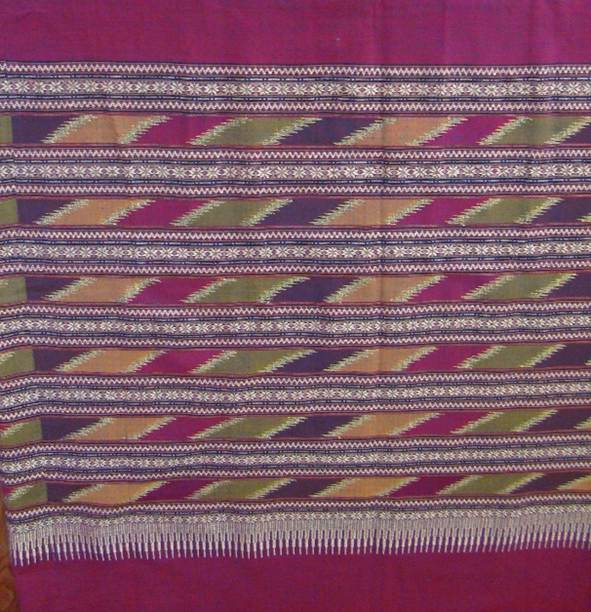

- Tapestry Weaving

Tapestry weaving differs from the basic tabby weave in that the weft is not woven from one to the other end of the arranged warp in one go, but is divided into sections with different colors depending on the pattern. The weft is then woven only in its designated sections. To achieve this, the warp in the section is picked up with fingers and the weft is guided under the picked-up warp. As a result, the weft appears to be “hanging on” to the warp, explaining the origin of the Thai terminology for the technique, ko luang (เกาะล้วง), with ko meaning “to cling on to” and luang meaning “to draw out”, denoting the drawing out of the warp with the fingers. Additionally, the warp is also divided into two sets, raised and depressed, which frequently exchange their positions throughout the weaving to allow the weft to be intertwined with all of the warp, reinforcing the strength of the fabric. The Tai Lue people living in the Northern region of the country are famous for this craft. Characteristics of traditional weaving are the elaborate geometric and angular patterns and “flowing water pattern”, or ลายน้ำไหล (Laai Nam Lai), a jagged alternating pattern resembling a flowing river, along with the usage of vibrant contrasting colors.

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

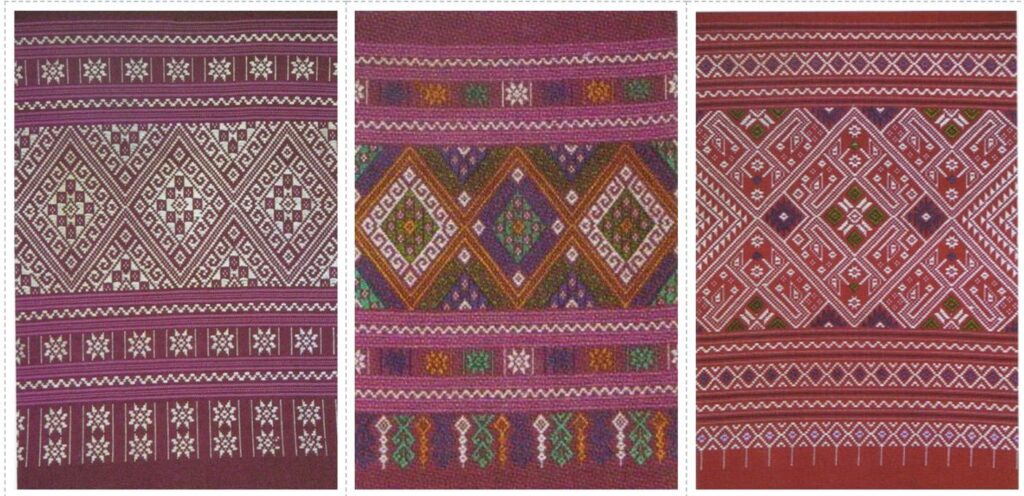

- Khit Textile

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Hailing from the Northeastern part of Thailand, khit (ขิด) textile boasts a highly complex style of weaving. At the center of the weaving process, the warp is divided into raised and depressed sets, with each group being carefully chosen and separated according to the desired pattern by using a flat piece of wood with a pointed head on one side, known as mai luuk khit (ไม้ลูกขิด). The warp is then held in place with a stick. This is repeated until the complete design is achieved. Thereafter, the weft is guided through the middle of the two separate sets of warps. To create a monochromatic motif on the fabric, the weft is carefully alternated between those of the same color and those of a different color than the warp. After the weaving, the sticks are stored on a device known as takoo yaao or khao toong teeng, which, in turn, help to store the design for further use. Khit textile yields a highly intricate and elaborate pattern, showcasing the artisanal prowess of the local people.

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Photo credit: Mantra Craft

- ฺBrocade

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Brocade or pha yok (ผ้ายก) produces highly intricate motifs by utilizing the separation of the warp into raised and depressed sets, similar to khit textile. However, in brocade, a special, often highly valuable, thread of silk, gold, or silver is used as the distinguishing weft to allow the motif to appear slightly raised from the background. Associated with luxury, brocade was historically used as a tribute from vassal states to their suzerain, or as a reward or pension from the court to the courtiers, and so was mostly worn by royalty and nobility. As a result, the textile usually sports traditional ceremonious motifs, including royal cones in varying sizes, stripes, leaves, diamonds, etc., arranged in a prescribed order. The patterns are intricately woven on virtually every inch of the fabric from the edge to the center and from top to bottom.

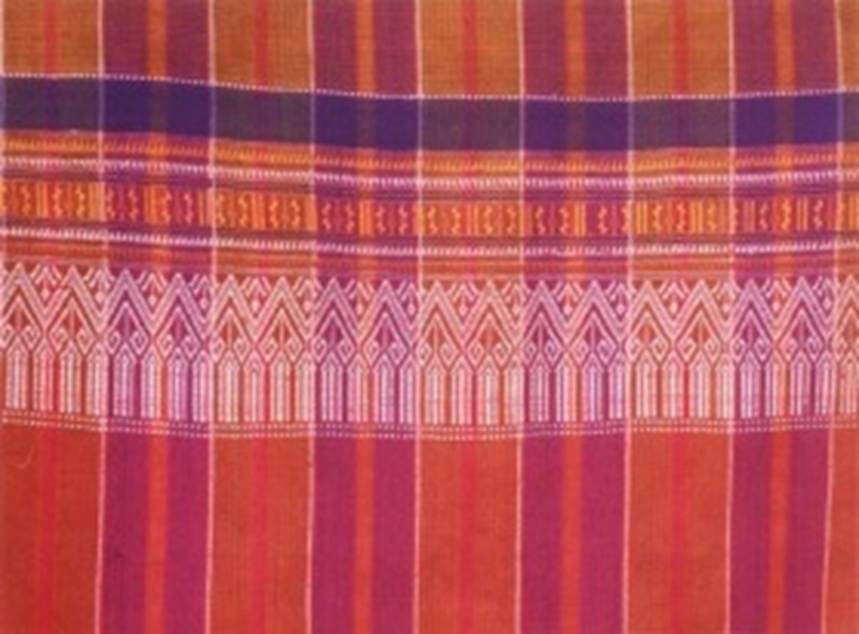

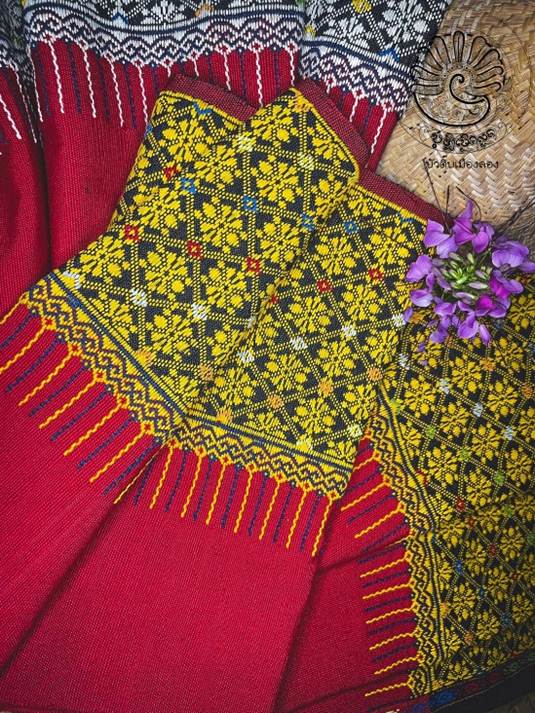

- Chok Textile

Photo credit: Museum Thailand

Photo credit: Museum Thailand

Iconic among the Tai Yuan people in the Northern region of Thailand, chok (จก) textile is a meticulous weaving technique involving the use of additional weft threads of varying colors, which are introduced into the fabric by using a pointed tool, such as pointed sticks or porcupine quills, to raise the selected sections of the warp, allowing the colored threads to be inserted underneath, creating highly elaborate patterns. The name of the technique, chok, meaning “to pick up”, is logically derived from this action.Traditionally, chok is usually used to introduce intricate embellishing to the bottom part of skirts (ผ้าซิ่นตีนจก, phaa sin tiin chok), which can sport many different motifs limited only by the weaver’s creativity.

- Phrae Wa Silk

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Traditionally created by the Phu Taiethnic in the Northeastern part of the country and used as sashes on special occasions, phrae wa silk (ผ้าไหมแพรวา) sees an amalgamation of the two previously mentioned techniques khit and chok.This allows for various highly complex and individualized ornamental patterns, each of which is usually woven in predetermined divided sections throughout the fabric, with the most elaborate pattern being featured at the center of the piece. Owing to the intricacy, the meticulousness of the process and the resulting unyielding beauty, phrae wa silk is often renowned as the “Queen of Thai Silk”. True to its name, with “phrae” meaning cloth and “wa”a traditional measurement unit denoting the length from the end of one’s outstretched arm to the other – equating to roughly two meters – the fabric usually measures around two meters in length.

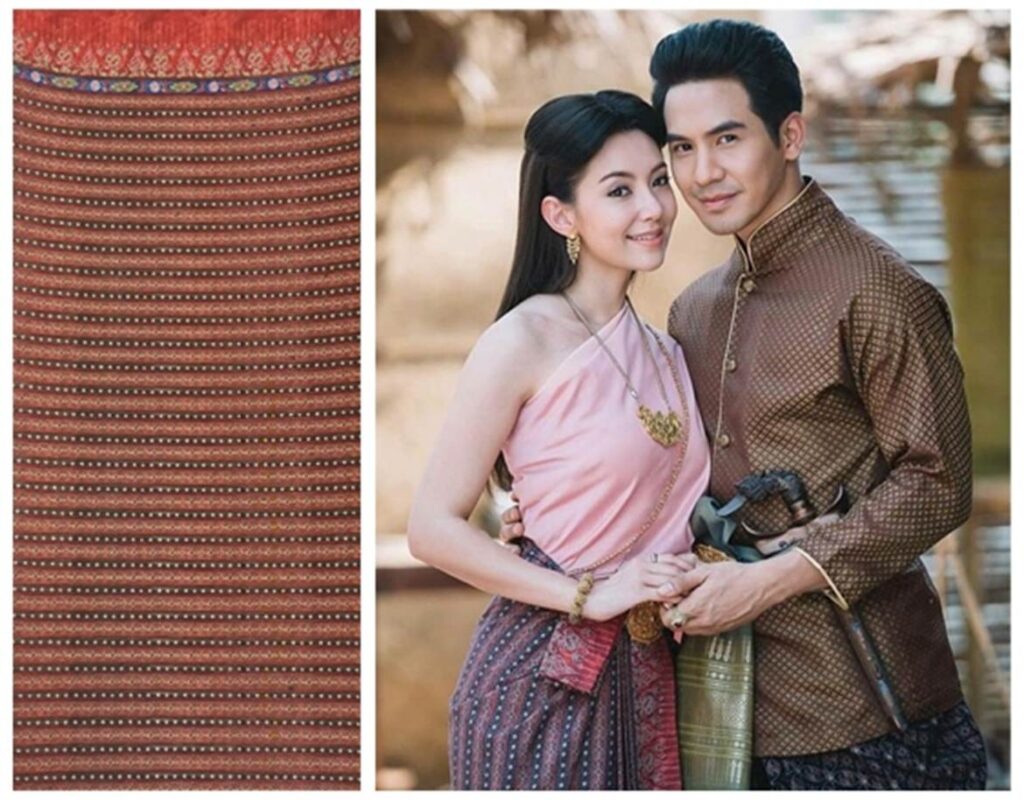

- Phraw Khao Ma

Photo credit: The Queen Sirikit Department of Sericulture

Arguably one of the most commonly used traditional fabrics, pha khao ma (ผ้าขาวม้า) refers to a rectangular checkered or striped fabric with varying sizes. The fabric is usually woven most commonly from cotton, but sometimes also from other readily available local materials, including silk and ramie. Each region of Thailand also sports its own variation on the pattern, adding, for instance, other special patterns into the mix or making it highly polychromatic. In any case, its versatility is unrivaled, as the fabric serves many everyday uses ranging from, but not limited to, being worn as a headband to being used as bedding, as a sitting mat, or even a diaper. Suffice it to say, the fabric is deeply interwoven within the daily life of Thai people. Interestingly, however, the name khao ma is postulated to have originated from the Persian kamarband, meaning “waist wrap”.

- Embroidery

Photo credit: Thai Tribal Crafts Fair Trade

Embroidery or pak pha (ปักผ้า) refers to the craft of creating patterns on a piece of fabric by using needle and thread, practiced the world over. In the context of Thai textile traditions, embroidery is often associated with royal traditions due to its delicate and meticulous nature, although the art is also practiced among the hill tribes. Thai embroidery may depict local folklore, scenes from literature and local or mythical flora and fauna. Among the hill tribes, the embroidery sometimes also holds a spiritual meaning. For instance, among the Hmongs, heart-patterned embroidery is used to symbolize the love of parents for their younglings, wishing them health, prosperity and safety.

- Beetle-wing Embroidery

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit The Queen Mother’s Dress

Photo credit: Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles

This technique is a variation of the conventional embroidery, which saw the use of jewel beetles’ fore wings (elytra) instead of threads as the main material for the ornamental patterns, resulting in a regal, glossy and verdant appearance. The rare practice, once a forgotten royal craft, with evidence suggesting its popularity dating back to the late 18th century CE, saw a resurgence in the 1980s under Her Majesty Queen Sirikit’s patronage.

- Nang Chang Sana

Photo credit: Thai Style Studio 1984

Ngan chang sana (งานช่างสนะ) is a term denoting the work of court craftsmen with expertise in textile arts, paper and leather crafts, encompassing not only the creation of a new piece of work but also the restoration and enhancement of pre-existing artifacts. Chang sana constitutes an important part of the traditional Chang Sip Moo, a collection of artist and craftsmen divisions under royal patronage with long traditions dating back to the Ayutthaya period (mid-14th to mid-18th century CE). The work of chang sana is on display in pieces associated with the royal court, such as costumes for khon, a type of royal theatrical performance, curtains in royal residences and regalia, often featuring highly elaborate and complicated patterns and the use of exquisite and luxurious materials, such as gold thread, jewelry and high-quality silk, as well as an integration of the work of craftsmen from other branches, such as metallic ornaments.

Photo credit: Thai Style Studio 1984

- Printed Fabric

Photo credit: Thai Culture to the World

Printed fabrics are made by applying pigments or dyes onto the fabric, which is then commonly fixed with heat to create a decorative pattern using certain types of printing mold, depending on the method. The design can later be recreated using the mold. In Thai traditional textile production, printing was virtually non-existent, only being used among royalty and nobility. One example of this is Siamese chintz or pha lai yang (ผ้าลายอย่าง), which was extensively used in the court during theAyutthaya and Early Rattanakosin periods (late 18th to early 19th century CE). The fabric featured intricate classical patterns designed by artisans within the royal court, which were then sent to be printed in India. There, the patterns would be printed using a wooden block to press the ink on to a white fabric before being dyed with the desired color, and polished. Later, the designs were also adapted and widely sold by Indian merchants, blending the original court design with traditional Indian designs. The chintz fell out of use after the introduction of Westernized wear in the mid-19th century CE but saw a resurrection in public awareness following the airing of the critically acclaimed period romantic comedy series, Love Destiny.

Photo credit: Matichon

- Batik

Photo credit: Creative Thailand

Batik (บาติก), derived from the Javanese term meaning “to dot”, is a textile tradition involving the application of hot wax to block out selected areas of the design before dyeing, allowing these to resist the dye, resulting in the desired pattern. The technique originated on Java Island in Indonesia, from whence it spread through the trade routes, as well as through Islamic influence into the Southern part of Thailand, where it since became widely used. Originally, the locals would paint the fabric exclusively for their personal use. However, with an increase in its popularity, the production of the fabric became largely standardized and industrialized. Traditionally, the textile features motifs influenced by Islamic traditions, including geometric and floral patterns.

- Hill Tribe Textiles

Photo credit: Tourism Authority of Thailand

Mentioned previously throughout the article, hill tribes refer to the various ethnic groups residing in the mountain ranges in the Northern, Northeastern, and Western parts of the country, including the Hmong, Karen, and Akha peoples, among others. Each hill tribe possesses its own culture, passed down from generation to generation within the community, resulting in a diversity in textile styles and techniques. Whereas some tribes might, for example, employ embroidery in their work, such as the Hmongs, others may prefer tapestry weaving or hand painting. Additionally, the meaning as well as the values behind each pattern can greatly vary from tribe to tribe. Suffice it to say, the unique designs and techniques constitute the identities of each tribe, through which a beautiful tapestry comprising various narrations of local pride, wisdom and expertise in craftsmanship can be admired.

All of these are but a glimpse into the tremendous inventory of diverse traditional styling and decorative practices within classical Thai textile production. Many more are still waiting to be uncovered on your next visit to the Land of Smiles!

Innovations and Global Appeal

Photo credit: Phathaisaihaisanook

Nowadays, the Thai textile industry constitutes a significant portion of the country’s export asset, taking in almost 111 billion Baht (~ 3 billion US dollars) in revenue the previous year, according to the Bank of Thailand. Furthermore, certain traditional materials, such as Thai silk, are widely recognized and coveted internationally. Consequently, modern designers are increasingly seeking to adapt traditional textiles into modern fashion, interior designs and accessories, uniting the timeless classics with the modern. Traditional textiles may also offer an alternative eco-friendly solution to the growing industry through its extensive use of natural dyes and locally sourced natural fibers. In this light, Thai traditional textiles may be a potential avenue for future innovations in the textile industry, paving the way for the Thai fabric industry to further solidify its position on the world stage.

Values Behind the Threads

Photo credit: Sirivannavari

Photo credit: Matichon

Photo credit: Phathaisaihaisanook

As noted, once a declining tradition, Thai traditional textiles have seen a great revival under the tremendous patronage of Her Majesty Queen Sirikit, becoming one of the most significant sources of national pride. Woven into the fabric is not only the exquisite material, but also a tapestry of rich and diverse narratives, of unique identities, and the culmination of age-old traditions passed down through countless generations among the various communities of the Land of Smiles. Additionally, the craft also embodies the artisanal expertise inherent in Thai culture, as well as the wealth of local wisdom in adapting locally available materials to bring about the conception of a magnificent product, reflecting a deep reverence for and connection with nature. The diverse geography contributes to the richness of styles and techniques unique to each ethnic group residing harmoniously within the country, which are, owing to the open-minded nature of the people, seamlessly and appreciatively incorporated into the main culture. The textiles also signify the adaptivity and creativity of artisans in continuing to further improve upon and develop the craft through the changing times.

Conclusion

Evidently, Thai textiles are not only a traditional art form, deeply rooted in the rich history and culture of the Land of Smiles, but also a living and constantly evolving tradition that continues to be awe-inspiring to both locals and foreigners. Of course, this article can only just scratch the surface of these diverse cultural goods. In this light, the next time you visit Thailand, places like Phrae province,Sakon Nakhon province, or any other textile community might pique your interest as the sources of some of the fabric mentioned in the article.

Photo credit: Bua Tip Mueang Long Clothes Store

Photo credit: The Cloud

For those wanting to take a deep dive into the world of Thai traditional textiles, take a visit to the Sustainable Arts and Crafts Institute of Thailand in Ayutthaya province, where various Thai traditional crafts are showcased and where you can also get your own piece of Thai fabric and support local artists. Or, visit the Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles in Bangkok, housing a collection of outstanding traditional textiles from all over the country. The world of Thai fabric is waiting for you to venture through and discover its richness and elegance.

at the Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles

Photo credit: The Grand Palace

Thai fabrics and textiles are treasured aspects of Thai culture and heritage. The craft reflects Thai people’s refined nature, creativity, and close relationship with their natural environment. Join us in exploring more stories of Thailand and the Thai people as we take you on a journey to discover the essence of Thainess.

Sources

https://www.jimthompson.com/pages/about

https://www.jimthompson.com/pages/timeline

https://researchcafe.tsri.or.th/potential-and-opportunity

https://www.thairath.co.th/lifestyle/life/2745916

https://www.culture.go.th/culture_th/ewt_news.php?nid=5866&filename=index

https://www.esanpedia.oar.ubu.ac.th/tint/?page_id=59

https://www.tcdcmaterial.com/th/material/6/textiles/info/MI00536-01

https://www.phakram.com/story-kram-sakol/

https://www.ngthai.com/cultures/51633/thai-mauhom-textile/

https://qsds.go.th/wp-content/uploads/2017/pdf/2013-11-04-yom4.pdf

https://www.britannica.com/topic/lac-resinous-secretion

https://www.thailandfoundation.or.th/culture_heritage/mat-mii

https://www.qsds.go.th/encyclopedia/viewWord.php?id_words=222

https://www.lib.ru.ac.th/journal/loincloth.html

https://www.thailandfoundation.or.th/culture_heritage/thai-style-embroidery

https://www.britannica.com/art/embroidery

https://www.britannica.com/topic/textile/Printing

https://www.library.wu.ac.th/content/siamese-chintz

https://www.matichonweekly.com/column/article_739908

https://thailandotop.org/batik-model/?r3d=batik-model-flipbook#24

https://www.batikguild.org.uk/batik/what-is-batik

https://archive-api.sacit.or.th/documents/media/book/media-book-I3AlZhLnLg.pdf

https://app.bot.or.th/BTWS_STAT/statistics/BOTWEBSTAT.aspx?reportID=976&language=TH

Author: Yodasawin Uaychinda

Editor: Tayud Mongkolrat